Atomic I/O letters column #130

Originally published 2012, in Atomic: Maximum Power ComputingReprinted here June 8, 2012 Last modified 16-Jan-2015.

Microwave oven not an acceptable substitute

Last week, my old GeForce 8800GT died. Garbage on the screen during boot, didn't make it to Windows. I stole the oldest PCIe graphics card in the world from my dad's computer so I could at least use 2D mode, and started shopping for a new card. Everything I can buy is faster than my old card, which would be nice, but I'd really rather not upgrade right now, for financial reasons.

But then I remembered reading about people who managed to fix flaky video cards by baking them in an oven to reflow the solder. Put board in oven at 190 to 200 degrees C for 5 to 10 minutes, dry solder joints get wet again, is the theory.

Bugger me, it worked. I'm a believer.

But while I was looking up how to do this crazy thing, I found this page from a guy who fixed his LaserJet with the oven trick, but then had to do it AGAIN six months later.

Am I going to have to do that too? It took my card three years before it went wrong; is it going to go wrong again, faster? What actually went wrong in the first place?

L

Unfortunately, you can't just shave 'em.

Answer:

I don't know exactly what problem your card had, but it was indeed probably the

solder. In the case of the fellow who has to cook his LaserJet circuit

board every six months, it's almost certainly the solder.

Standard old-fashioned electronics solder is an alloy of tin and lead, in about a 60:40 ratio.

Tin/lead solder is good because both metals are cheap (and lead's considerably cheaper than tin), and the mixture has a pleasingly low melting point, and the lead cures the tin of two scientifically fascinating, but very irritating, habits. Bad habit one is "tin pest", in which pure tin below 13.2 degrees C slowly converts itself into a powdery grey allotrope that doesn't conduct electricity any more.

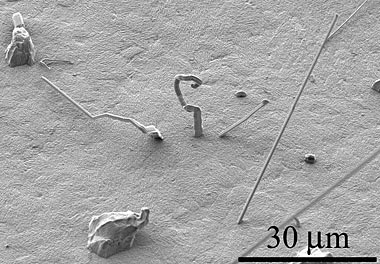

Tin's second bad habit is the formation of "whiskers", super-thin metallic hairs that slowly grow out of certain metals and alloys. Tin whiskers can easily grow long enough to electrically connect components on circuit boards that shouldn't be electrically connected.

Tin pest is seldom a problem in the real world, because if the tin is alloyed with almost anything, it won't convert unless the temperature is a lot colder or you wait a lot longer. Tin whiskers are also curable by alloying; plenty of lead in the alloy does the job nicely.

But lead is poisonous, and so the electronics industry is moving away from it. Already has moved, in most cases.

(If you're an electronics hobbyist, tin/lead solder is considerably easier to work with than lead-free, so you should probably keep using it, along with decent ventilation to keep vapour out of your lungs.)

The simplest formulation for non-toxic lead-free solder is just tin by itself. Many manufacturers used that, in the early lead-free days, to coat the legs of components. The actual solder then used to attach the components to the PCBs was more than 99% tin, less than 1% copper.

This all seemed to work pretty well until, a year or three later, these early lead-free circuit boards started failing at alarming rates. Most electronics keeps itself warm enough to avoid tin pest, but tin whiskers grew with great enthusiasm, especially from the pure tin plating on component legs. The ultra-thin whiskers can only conduct a trickle of current without being melted by their own resistive heating, but tiny trickles of current are the stock in trade of most integrated circuits. So one minuscule whisker can kill a graphics card, or a whole computer, or a printer.

Old-style tin/lead solder melts at only about 185°C, so you can easily "reflow" a PCB in a household oven at less than 200°C. Many hobbyists have dedicated a toaster oven to this task, to prevent lead, epoxy and who-knows-what-else from accumulating from vapour in their actual food oven.

The melting point of pure tin is almost 232°C, though, and 99.3%-tin 0.7%-copper solder needs around 227°C. So an oven at 200°C shouldn't be able to melt the whiskers.

Oven thermostats aren't very accurate, though, and circulating air from, especially, the flames in a gas oven, can easily be considerably hotter than the overall oven temperature. So the guy with the LaserJet that needs re-baking every six months probably has a lead-free circuit board that's growing whiskers, which melt away again in the oven.

The Case of the Vanishing Speakers

Every few boots my Windows 7 x64 computer just... loses... my Logitech USB speaker drivers, and has to re-download them. They're just little stereo speakers, not a surround set. I think it happens when I've got other USB stuff plugged in when I reboot, but I'm not sure.

It's not the most annoying thing in the world, but it does make me wonder if there's something going wrong deep in the guts of Windows. I remember stuff being redetected every boot in Win98 so I ended up with 20 monitors in Device Manager, but Win7 only ever seems to see one set of speakers. It just keeps... reacquainting itself with them.

Any idea why?

Darwin

Answer:

I don't know for sure why this is happening in this one particular case, but I can give you a general explanation.

Simple USB audio devices like a pair of speakers should just use drivers that're built into all modern OSes. But this is another of those cases where beautiful clean specifications turn into a snake-fight in a mudhole once the free market's left alone with them for five minutes.

There isn't, you see, actually a standard basic USB audio driver, in the same way that there are standard drivers for mice and keyboards. It looks as if there's such a driver, to Windows users, most of the time. But Linux users know that USB audio devices actually come in numerous flavours, and may not admit to being audio devices at all.

A set of speakers may, for instance, swear Scout's-honour to Windows that it is in fact a keyboard, on which keys mysteriously never seem to be pressed. When you install the drivers that come with the speakers, they reach out to every "keyboard" plugged into the computer and poke them in a mystic Masonic sort of way, and the one that gets the secret handshake right is then connected to the audio subsystem.

But then you reboot with more USB devices connected, or things plugged into different sockets. Windows would be perfectly able to sort this out if everything told the truth, but when all it sees are a bunch of "keyboards" on different sockets, the driver-installation procedure has to be done again to see which of these devices actually are keyboards, and which are waiting for a secret dog-whistle.

Practical network engineering

If I dug a hole through the middle of the planet to the other side, lined it with unobtainium to keep the magma out, and ran a similarly fireproof Ethernet cable through it, how long would it take for the electrons to make the round trip? What would my ping time be?

Jason

Answer:

Mobile electrons in a conductor move incredibly slowly. The net "drift

velocity" is determined by the cross-sectional area of the wire and the current passing through it, but even at

high currents you're still only talking millimetres per second.

When electrons move, though, they push the electrons in front of them along, and those electrons push more, somewhat like water in a hose. This wave-front of motion propagates extremely quickly - close to the speed of light in vacuum, for an uninsulated chunk of metal. A typical multi-conductor insulated cable still manages something like two-thirds of c, or about 200,000 kilometres per second.

A 12700-kilometre trip (the approximate diameter of the Earth) at that speed will take about 0.064 seconds, so your round-trip latency, ignoring processing at the far end, would be about 127 milliseconds.

Unfortunately, though, the maximum cable length for 10/100/1000BaseT Ethernet is only a hundred metres. You can stretch that a bit and get away with it, but stretching it by a factor of more than 60,000 is inadvisable.

(A hole dug from us here in Australia would also come out in the Atlantic Ocean, but let's presume you manage to hit the Portuguese Azores or something, and there's someone there who wants to play Counter-Strike with you.)

Your Comic-Book Science Machine could probably make you a superconducting Ethernet cable, but superconductors only pass direct current with no loss, and Ethernet is high-frequency alternating current. So you'd still be stuck with thousands and thousands of repeaters of some sort. Unless you went for optical fibre, of course; I'm sure your Science Machine could also make you an incredibly long fibre of magically non-dispersive glass to do the job. Conveniently, the speed of light in glass is also about two-thirds of c. So there you go; about 64 milliseconds, each way.

In real-world situations, the raw "signal speed" of the cables often doesn't make a big contribution to the total ping time. Satellite Internet is so lousy for action games because you're bouncing your signal off something in geostationary orbit, about 35,786 kilometres above the equator. That gives you about 240 milliseconds of light-speed signal propagation time, for the signal to get from you to the satellite and from the satellite back to the ground somewhere else, plus another 240 milliseconds for the reply to get back to you.

(Old-style "one-way" satellite, where your downstream channel comes via geostationary orbit but your upstream travels via dial-up modem, may not actually be much worse in total ping time, depending on how much upstream bandwidth you need.)

You'd need the thick end of 50,000 kilometres of wire to be waiting even 240 milliseconds, the one-way geostationary latency, for an electrical signal. The circumference of the whole planet is only about 40,000 kilometres.

Real-world network latency comes, instead, from the servers and clients, and from the layers of routing and switching and firewalling between them. Traffic volume has an enormous impact too; little ICMP ping packets can behave (and/or be treated) quite differently from larger TCP and UDP game packets. (This is why pinging a server from the command line can give results quite different from perceived latency in games and other software.)

So mere through-the-planet tunnelling machines won't, I'm afraid, give us really snappy trans-planetary gaming experiences. We're just going to have to wait for traversable Lorentzian wormholes. And unfortunately, poking a Cat 5 cable through a black hole always seems to violate the minimum bend radius.