Science versus SoftRAM

Publication date: 5 August 2013Originally published 2013, in PC & Tech Authority

(in which Atomic magazine is now a section)

Last modified 05-Aug-2013.

In his 1974 speech that's since come to be called "Cargo Cult Science", Nobel-Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman explained the chief difference between science and "pseudoscience".

Pseudoscience is non-scientific activity that apes the forms and conventions of real science, just as the Pacific-island cargo cultists built faux runways and wooden radios and marched around and saluted each other, in the faithful expectation that this would cause the aeroplanes full of wonderful cargo to come back. Or something.

That chief difference between science and pseudoscience, Feynman said, is that in real science you must take care to not fool yourself, because "you are the easiest person to fool".

It doesn't matter how clever you are. It doesn't even matter how knowledgeable you are. If you don't take pains to avoid fooling yourself, you will end up believing things that aren't true.

Like, for instance, the idea that American GIs caused cargo to manifest by the performance of various rituals.

For a more recent example, look at Syncronys SoftRAM.

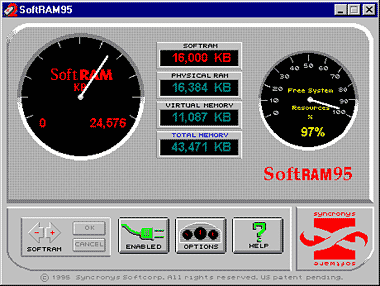

SoftRAM was a Windows utility that went on sale in 1995 for Windows 3.1 and the then-new Windows 95. Syncronys said it used clever compression tricks to double the effective memory in your computer, which was a big deal when 16 megabytes of memory cost $US500.

A program that'd turn your four-megabyte 386 into an eight-megabyte machine able to run Win95 at a speed better than same-day service sounded like a great idea. And SoftRAM only cost about thirty bucks US. (The list price was $US79.95, but this was when there was always a big difference between list and "street" prices for PC software.)

What SoftRAM actually did, though, was enlarge the swap file, and multiply the RAM your computer reported having by two.

That was it.

SoftRAM did nothing else, except slow your computer down a bit. It was a total scam.

Some other RAM compressors, like Connectix's inventively-named "RAM Doubler", actually did something. But SoftRAM did not.

When this came to light the US Federal Trade Commission made Syncronys recall their products, and told them to give refunds to any customers who asked. A lot of customers asked, but many were still waiting to get their money back when Syncronys went out of business in 1999.

What, you may now be wondering, does this audacious but in the end unsuccessful scam have to do with science and pseudoscience?

Syncronys sold hundreds of thousands of copies of SoftRAM. 600,000 units just of the Windows 95 version, according to Germany's venerable C't magazine, which was instrumental in exposing the scam. SoftRAM was, according to a possibly unreliable Syncronys press release, the best-selling Windows utility software for months on end.

How do you sell that many copies - into a much smaller market than exists today - of software that does nothing?

You take advantage of people's natural aversion to the scientific method, that's how.

It was easy for anyone to test SoftRAM. Time some task that's not very fast because you don't have enough RAM and are beating the heck out of the swap file, then install SoftRAM, and time the same task again. If you're a big fancy computer magazine you could even have two identical computers side by side, one with SoftRAM, one without.

But for months, it seems none of those big magazines did such a test.

In a press release at the end of 1995, Syncronys gleefully reported that the November PC Today rated SoftRAM as better than RAM Doubler and two other actual real memory-compressors.

Syncronys also reported 82% customer-satisfaction ratings, which seems plausible enough. You don't sell hundreds of thousands of units of a product with bad word-of-mouth. It wasn't hard to find people who tried SoftRAM and thought it was great, or at least OK.

Outright scams can be difficult targets for the scientific method, because you don't generally expect a commercial product to be completely worthless. If I'd done a proper test and found SoftRAM didn't do anything, my first assumption would have been that I'd messed up the test somehow.

(When the scam started to unravel toward the end of 1995, Syncronys played into this by claiming the software had some "bugs", which mysteriously caused anybody who tested it properly to find it didn't do anything.)

Some print publications may also have kept their reservations to themselves, lest they be sued by Syncronys. It's also perfectly defensible to decide not to print a review of a dodgy product at all, if you use the same pages in your magazine to review something actually worth buying.

A lot of early reviews of SoftRAM, however, expressly stated that it did work.

The only honest ways to come by this impression are by not testing anything properly at all and just going on your unreliable human gut instincts, or by actually messing up your tests, quite severely.

Humans routinely fail to use controlled tests and critical thinking when it really, really matters. Never mind wasting money on useless software - how about whether you should see an actual doctor, or a psychic aura therapist, about that funny lump you just found? Or deciding who to vote for? Or whether it makes mathematical sense to go into astonishing debt just so you can "own" a house?

Science is hard. But you've got to do it, surprisingly often, if you want some actual factual knowledge about not just your computer and car and health and personal finances, but pretty much everything else in your life too.

Also, it'll help keep your money out of the pockets of scumbags like Syncronys.