Dan's Long-Awaited Photo Tutorial-ish Thing

First published 5 December 2003.Last modified 03-Dec-2011.

Every now and then, somebody asks me how I make the pretty product shots I use in my reviews.

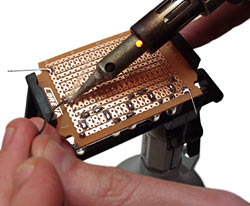

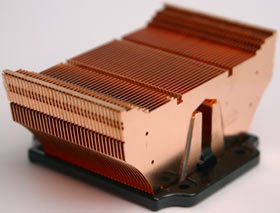

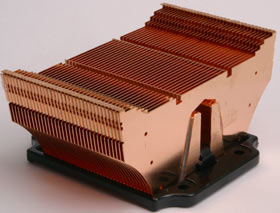

You know; this sort of thing.

No, wait.

Yeah. That's what I mean.

OK. Here's how I do it. At the moment, anyway. I confidently expect many readers to tell me better ways to do many of the things I talk about below, whereupon I'll both incorporate the better methods into my workflow, and update this page so I can pretend I knew them all along.

I wouldn't, as you may have guessed, call myself an expert photographer. I take a lot of pictures, though, and I'm halfway competent at making good product shots (which is to say, I've made some very nice looking product shots if I do say so myself, but I've probably taken far too long to make 'em).

You do not need a professional photo studio to take good pictures of small-ish objects - computer hardware, gadgets, your Transformers collection, whatever. You do not even need an elaborate amateur photo studio, with light stands and flash reflector umbrellas and backing paper roll dispensers and other stuff that'll take over whatever room you set it up in.

You also don't need a fancy-pants digital camera. I've got one, but if you only need Web-resolution output, there are now lots and lots of relatively cheap digicams, new and second hand, that'll do just fine.

If you don't have a passable camera already, go to a good review site and hunt one up. Penny-pinchers should see what was the New Hotness three or four years ago then buy a good used example. If you're richer or just less patient, go and grab yourself a well-reviewed consumer Olympus or Nikon or Fuji or, yes, even Sony. That'll do.

You can now get yourself a real live digital SLR, with a lens, for less than a thousand US bucks. You can spend about $US200 more than that on an integrated-lens camera, if you really try, which is pretty amazing.

The deal with DSLRs used to be that you paid easily twice as much just for the DSLR "body" as you would have for a nice "prosumer" point-and-shoot camera, and then you had to find money for lenses. And other DSLR users would laugh at you if you bought a great big horrible cheap-ass slow-as-shit zoom lens.

Now, though, DSLRs aren't quite as far into the luxury end of the market, especially if you've got a film camera already that uses compatible lenses. Some people who buy DSLRs probably shouldn't, but if you know what you're getting into and aren't frightened by sensor cleaning, DSLRs are great.

(And not just because they can accept the kind of lenses that're likely to cause U.N. weapons inspectors to come knocking. Don't expect change from $US100,000 for that particular item, by the way.)

Pro cameras seem to hold their value quite well. What this means, to me, is that you shouldn't buy a used DSLR, unless you manage to find an unwanted-gift sort of bargain on a new one.

If Canon didn't keep shoving the pro-cam entry point down with models like the EOS-10D and, particularly, the EOS-300D, then something like an old EOS-D2000 (the exact same camera as the Kodak Pro DCS520, except for the badges) would be a good option. But it's hard to find a D2000/DCS520 body in good condition for a lot less than $US750. You don't want something that's been bounced around for four years by some war correspondent or paparazzo, but even a carefully cared for example will probably need a new, and not cheap, battery.

So, coming back to earth: A camera that costs less than $US300 brand new will do just fine, and you can make do with gear considerably cheaper again.

You certainly don't need a whole bunch of resolution if you're shooting for the Web; for Web work, megapixels for their own sake are nuts.

An 800 by 600 image is a big image on the Web, and even if you've only got a 1600 by 1200 camera, you'll still be throwing away three out of every four pixels to scale to 800 by 600. If you've got a "six megapixel" camera like my D60, 800 by 600 is less than 8% of your pixels.

You need to allow for a little extra resolution, because you're never going to perfectly frame your subject. If you've got a really low-res camera, it pays to spend time getting the framing as close to perfect as possible in the first place, because every pixel counts. With most modern cameras, though, you needn't be too careful.

You can't use any old camera, mind you.

Regular readers will know that I have great affection for "baby" digital cameras, the hilariously cheap plastic jobbies that are available in so many different models these days. You can just barely wrestle tolerable product shots out of one of those, if you've got one with adjustable focus, and you take a whole lot of pictures for every one you keep, and you only need Web resolution.

Really, though, you need a proper camera for this kind of work. Save the toy-cam for nightclubs, parasailing and handing to seven-year-olds.

Whatever camera you end up with, you need to know how to use it. If you bought the thing from a bloke in a pub and have no user manual, then you're going to have to figure out how to set shutter speed and aperture in manual mode. Or, if you've got a camera with no full-manual mode, how to use aperture or shutter priority mode. Or, if you've got a no-sharp-corners consumer camera, at least how to set exposure compensation. Tell me you can at least do that.

Many consumer digicams these days have a proper manual mode, where you can dial up whatever shutter speed, aperture, white balance and sensitivity combination you like and take a picture. Every half-decent digicam has at least an exposure adjust mode and a selection of canned white balance settings. That's enough, in combination with a passable image editing program.

(Is all of this Greek to you? Get a book.)

Yes, you will need to post-process your images. The big deal about pro photo studios is that they let the photographer produce images that need little or no post-processing; this really, really matters when you've got 324 products to photograph for a catalogue and only one day to do it in. In a high-throughput situation like that, you need to get pretty much finished images right out of the camera, and that means immaculate exposure, perfect backgrounds and gorgeously prepared subjects.

If you can afford to spend a few minutes per image, though, you can get away with a much simpler photographic setup, and a number of other sins.

If you've got no money, or would rather just not spend any, the image editing program of choice is The GIMP. It costs not a penny, and it has most of the features of Photoshop.

If you try The GIMP and it doesn't cut it for you, there's Paint Shop Pro, and there's also Photoshop Elements, which can do most of the stuff that most people want to do with the full version of Photoshop, but which is far cheaper.

In this tutorial, I'm going to talk about Photoshop 7, because that's what I'm using at the moment. I'm not going to be doing anything very obscure, though; it's not difficult to perform basic image prep tasks in any image editor.

The point of it

If you just want pictures of stuff to go with your review, or on-line store listing, or eBay advertisement, or whatever, then you don't need this tutorial. Take a few shots from different angles of the thing, preferably lit by indirect sunlight, but on-board flash will do. Now pick whichever ones look best, and you're done.

There's no point going to any more trouble if a from-the-hip happy snap will do for your purpose. But if there's some point to making pretty images - if only because it feels good to make something beautiful, rather than something merely adequate - you can.

Beautiful and informative pictures are best, but ugly and informative is OK. No picture at all comes third. Beautiful but meaningless comes fourth, and only the truly talented can take pictures that're both ugly and meaningless.

Regular people with cheap gear whose studio is a dining room table really can take photos that look as if a professional photographer took them. Your work can be good enough for publication in magazines, or in high-class catalogues, or anywhere else an expensive pro photographer's work might go, provided your camera's got high enough resolution for the application.

So here's what I do.

This isn't really a going to be a tutorial, because there are too many choices to make at various stages for me to be able to define a single simple workflow. Instead, it's one of my trademark stream-of-consciousness rambles, with practical advice intermixed with long explanatory technical passages.

Enjoy.

Location, location

If you have enough room, time and money to set up a real photo studio, then that's great. If all you've got is a desk or kitchen counter, though, that'll do - well, as long as you don't need to photograph anything that's too big to fit there.

If your photo-taking area is just a corner of your office, or a white-sheet-draped bed, or some similarly gimcrack setup, you can face various other problems.

Space can be a big one; there's always likely to be room to photograph something the size of a mouse, but if you're photographing something the size of a PC case then you may have room to put the thing down, but not be able to get far enough away from it to get the whole thing in frame, if your camera doesn't offer a wide enough wide angle setting. Even if you've got an integrated-lens camera you can deal with this problem without moving your photo studio out into the garden, though, as long as the camera can accept an add-on wide angle adapter.

Holding steady

Get a tripod. If you don't mind your camera not being very far off a solid surface then your camera support can be as simple as a bag of beans, but a tripod is pretty much essential for proper positioning flexibility.

Your tripod doesn't have to be a good one. Any old thing with a standard thread on top of it will do for basic product photography; you just want something that can hold the camera pretty much still. Practically every digital camera has a standard tripod socket on the bottom of it. Even a lot of toy-cams do.

You're shooting indoors, so your tripod doesn't have to be heavy and windproof or super-vibration-damped. Go buy yourself any old cheap super-lightweight aluminium tripod - the kind of thing that a "real" photographer might possibly keep in the boot of his car just in case his proper tripod falls down a storm drain.

Velbon, for instance, make some quite good expensive tripods (including some excitingly pricey carbon fibre models), but their basic models, which may well be all you'll find in your local discount photo shop, are cheap and cheerful. We're talking $US25 to $US50, here.

There are lots of even cheaper new tripods on eBay, but you'd do better to buy a used brand-name tripod second-hand. Cheap and cheerful is one thing, but telescopic leg locks that slip and heads that won't stay anywhere near where they're put aren't worth paying anything for.

Why do you have to get a tripod? Glad you asked.

Tripods let you do two things.

One, they hold the camera still so you can take pictures with long exposure times. A general rule of thumb is that you shouldn't try to hand-hold a shutter speed that's slower than one divided by the 35mm-equivalent focal length of your lens. In English, this means that most cameras at full wide angle have a no-tripod shutter speed limit of around 1/30th of a second - and a lot of product shots are taken at a more telephoto focal length than that.

You don't necessarily need slow shutter speeds; if you're taking flash photos, you don't. The duration of the actual photo-taking flash is only around a millisecond.

But you probably won't be using flash, if you want the best results from consumer cameras. I'll come back to this.

The other thing a tripod does is let you take a series of shots with the exact same framing. So you can line up just the composition you want, with the subject taking up pretty much the whole frame and thereby maximising your camera's useful resolution, and then play with the exposure without worrying about chopping the corners off the thing you're photographing.

Tweaking exposure up and down is called "bracketing", and it's something you should do a lot. Go ahead and let the camera's auto-exposure show you its best guess at the shutter speed you should be using for the aperture you've set (that aperture will be small, for reasons I'll get to in a moment). Then, set the shutter speed (or flash power, if you're using flash) a few notches lower, and take a series of pictures with higher and higher settings until you've gone well past the suggested setting.

While you're learning, if the camera reckons you need a 1/60th second exposure, go ahead and try everything from one second to 1/1000, if you like. Most of these pictures will be severely over- or under-exposed, but this'll illustrate the effect of exposure changes admirably. Because all vaguely recent proper digicams save images with EXIF data, including focal length, shutter speed, aperture, ISO sensitivity and so on, it's easy to tell after the fact what settings you were using to get a shot, without using any other memory aids.

If your camera doesn't have manual exposure controls of any kind, don't panic. Unless it's a real cheapie it should still have exposure lock, where the camera decides on its focus and exposure settings when you half-press the shutter button. So half-press with the camera pointed at some part of the subject that you think is representative of its overall lightness, then re-aim the camera with the button still half-pressed, then fully depress the button to take the shot. Do this over and over, aiming at a different part of the subject every time, and you'll have a good chance of getting a nice shot.

As I've written on previous occasions, the secret to great photography is very large amounts of bad photography.

Anyway. Tripods. If you get a tripod with an extensible centre column - most full-size tripods have one - then you should try not to use it. Yes, the columns with little crank handles are fun to wind up and down; feel free to play with yours until you get that out of your system. Cranking the camera up on a wavy pole, you see, neutralises the stabilising advantage of the tripod.

Try to get into the habit of calling the centre column the "idiot stick". The less of its length you ever use, the better.

(The exception to this rule is if you're only, as I mentioned above, using the tripod to keep the camera aimed in the same direction so you'll get a series of identically-framed shots, and not actually using a slow enough shutter speed for a little bit of idiot-stick wiggle to give you blurry pictures.)

For the same reason, if your photographic environment has thick carpet with a luxurious spongy underlay, then you might do well to relocate to the garage. If that's not possible, put down a hard plastic carpet protector or other rigid mat to help keep the tripod steady.

Why do people buy more expensive tripods? Partly because they're tougher, but mainly because they're nicer to use.

If you get a decent tripod, then the head will stop exactly where you put it, for instance. So you won't line up your perfectly framed shot, then let go of the head handle and see the camera's aim bounce back the way it came.

The dividing line between quality and cheap-and-cheerful tripods is easily drawn. If the tripod's head and legs are one inseparable unit, it's a cheapie. Serious tripod "legsets" and heads are separate items, and usually sold separately.

You don't have to spend a fortune to get a nice tripod. I use a Manfrotto 190PRO (in the US, it's sold as the Bogen 3001PRO) with a funky grip-action 222 ball head (Bogen 3265). The two together cost about $US200.

There are lots of other advantages to more expensive tripods, but for domestic product photography purposes they're all pretty much irrelevant. You're not toting your tripod up mountains and thus wanting a super-lightweight carbon-fibre number, you're not standing on windswept rocks taking pictures of whales, you're not looking for something that'll let you get a ten-foot leg-spread yet only four inches of head height, and if the leg clamps on a cheapo-pod break or wear out, then you can always just go and buy another one.

For more professional information about tripods than you need for these purposes, start here.

Remote control

Still on the vibration-avoiding tack - to keep the camera really still when taking tripod shots, you need a remote release. This particularly matters for super-close-up work; the more magnification there is, the more disastrous the camera vibration that comes from pressing the shutter button becomes.

Traditionally, a remote release is something on the end of a cable (a switch, in modern cameras; a bike-cable plunger or pneumatic-hose arrangement for old ones) that works just like the shutter button. Digital SLR cameras can use the same cable releases as their film cousins.

Practically no integrated-lens point-and-shoot digital cameras have a cable release feature, but remote controls aren't unheard of. Various Olympus cameras, including my old C-2500L, have them; they'll work from some distance away.

If you don't have a remote, then you can:

1. Wing it using the regular shutter button and see if the results are good enough.

(Quick tip: Take a series of pictures and, when you copy them to the computer, just keep whichever one has the largest file size, because that's probably going to be the least blurry one. A few cameras have a feature like this built in.)

2. Use the self-timer.

On the minus side, waiting ten seconds for the camera to take the picture (and another ten, and another ten, if you're trying multiple exposure settings...) is a bit of a pain. On the plus side, that ten seconds will definitely give any residual vibration in the camera/tripod system time to dissipate!

The self-timer's also handy if you need both hands to do whatever you're photographing, of course.

Mysterious settings

To take good, sharp, bright pictures of relatively small objects, you need to use a small aperture.

The aperture, as I explain in my ancient piece here, is the size of the hole that lets light into the camera. The piece of glass on the end of the lens may be, say, 30mm in diameter, but that's not the aperture; inside the lens there's a baffle of some sort with a hole in the middle. If you can change the size of the hole (which you usually can), then the lens has adjustable aperture.

The commonly heard but not well understood "F-stop" or "F-number", which is explained here better than I'm probably about to, is the focal length of the lens divided by the aperture. So while high F-numbers are associated with small apertures, they're not the same thing.

This isn't just a piece of trivia. It explains some weirdness that we'll hit in a moment.

The F-stop is useful in telling you one thing - the brightness of the image that makes it to the sensor. That's inversely proportional to the F-stop squared. So f5.6 gives you a quarter of the image brightness of f2.8, and will require four times as long an exposure, all other things being equal.

Stay with me, here.

Small aperture settings are necessary for good product photography because smaller apertures give you more depth of field - a larger range of distances from the lens in which things will be acceptably sharp, for a given focus setting.

Shoot a subject that's close to your camera with the camera set to a large aperture and you'll find it impossible to get the whole thing in focus (unless you're using a wavy-fronted digitally processed miracle lens).

It seems to be traditional to demonstrate depth of field with pictures of chess pieces, so I won't.

This picture was shot at f4.5, the lowest F-number my everyday zoom lens can manage when it's zoomed in all the way.

This lens can manage f3.5 at full wide angle - many zoom lenses have a smaller minimum F-number at full wide angle settings than at full telephoto, which is not surprising when you know how F-numbers are calculated. Lenses that don't have different F-numbers at different zoom settings are changing their aperture as you zoom.

Here's the same subject, but with the lens stopped right down to f32, the smallest aperture it supports (at full wide angle, its smallest aperture is f22). When framing the shot, cameras normally leave their aperture all the way open, so you don't see the depth of field that you're going to get when you take the picture. They do this because a small aperture will make the viewfinder dim.

The focus point is one third of the way into the full depth of field, so you shouldn't focus right on the nearest corner of the thing you're shooting. Even with the best will in the world, though, large apertures and small subjects don't mix well.

High F-numbers give more depth of field, but they also create more diffraction distortion. The smaller the aperture, the more the lens acts like a lensless pinhole camera, which has infinite depth of field but lousy sharpness at all distances.

For most close-up product shot purposes, though, you should crank that aperture down as far as it'll go. A bit of overall sharpness loss is acceptable in return for better depth of field.

Small depth of field can, by the way, be quite desirable when you're trying to emphasise the foreground and avoid distracting the reader with stuff in the background.

And, of course, it's also good for portraits.

The closer you get, though, the shallower your depth of field becomes at a given aperture.

For extreme close-ups, large apertures give so little depth of field that it becomes very difficult to clearly show the whole of pretty much anything.

Most digital camera owners will now be wondering why their camera doesn't support high F-numbers. Most don't, you see.

Nikon's popular Coolpix 4500, for instance, is a great camera choice for product shots (and for general photography, too). But its minimum aperture setting gives only f7.5 at full wide angle and f10.3 at full telephoto.

Minolta's ton-o-zoom Dimage Z1 (a great camera for the money, but with a lens that ain't too sharp, which is not surprising for a cheap 10X optical zoom unit) tops out at f8 as well. The fancier and more expensive Dimage A1 goes to f11.

Even Sony's king-of-the-point-and-shoots, the DSC-F828, goes to only f8.

My old Olympus C-2500L has a grand total of two possible aperture settings. The "small" setting is only f3.9 at full wide angle, and f7.8 fully zoomed. The similarly old Sony DSC-F505 I compare the C-2500L to here tops out at f8.

Digicams that can only manage f8 or f11, though, are still perfectly fine for photographing small objects, with decent depth of field. The reason is because they've got small sensors. This is tied in with one of the great confusing issues of modern photography: Focal lengths.

The "focal length" of a lens has nothing to do with its physical length, or its minimum focussing distance. It just tells you how far away from the image sensor a pinhole would have to be to give the same field of view as the lens does.

It doesn't matter what sort, or size, of sensor is sitting in the back of the camera behind a given lens. Fingernail sized sensor, tennis court sized sensor; the focal length of the lens will remain the same.

This isn't terribly informative, though, because a smaller sensor will see less of the image that's being projected by a given lens. The focal length is the same, but the field of view isn't, if the sensor size changes.

For this reason, digital cameras have "effective" or "equivalent" focal length specifications, which allow people to easily compare the field of view of cameras that have different-sized sensors or film. Cameras with sensors smaller than 35mm are now commonly specified with "35mm-equivalent" focal lengths.

(Digital cameras with sensors bigger than 35mm film are still very exotic, but larger-than-35mm film cameras are relatively common, and cheap, even.)

A 50mm lens on a 35mm camera will give you about a 40 degree horizontal field of view (which makes it a "normal lens"). A digital camera with a zoom lens that's set to a "50mm-equivalent" position will do the same.

If, in this case, the digicam's sensor is half the width of a 35mm frame, then the actual focal length of the lens it's got will be 25mm. But this isn't of much interest to a photographer who just wants to know how much of the world will be visible. Big sensor, little sensor, tiny goblins; who cares what's in there.

A 35mm film frame's 35.8mm wide. The sensor in my EOS-D60 is 22.7mm wide. The common "11mm" digicam sensors (also, in a triumph of obscurantism, referred to as "2/3 inch") have an 11mm diagonal. They're 8.8mm wide.

Say you've got a lens for a 35mm film camera that has a fixed 50mm focal length and a fixed 6.25mm aperture. That makes it f8.

If you attach that same lens to a digicam that has an 11mm-diagonal sensor, that sensor will see only 8.8/35.8 of the field of view that the 35mm film frame did.

This means the lens, on this new camera, will now have an effective 203mm focal length, in 35mm terms. Even though its actual focal length hasn't changed at all.

Because the aperture hasn't changed - it's just the size of the hole the light's coming in through, and it's still 6.25mm wide - and the actual focal length hasn't changed either, the F-number also doesn't change. The lens is still f8, no matter what camera it's on.

The smaller sensor, though, means that f8 on the digicam doesn't behave the same as f8 on the film camera. Because the sensor's seeing only the middle bit of the projected image, you can actually apply the focal length multiplier number to the F-number as well, when you're working out depth of field.

Divide the 35mm-equivalent focal length by the aperture and you see that this lens behaves as if it had an F-number of 32.5. Large depth of field. Hurrah.

The lenses that're actually used in point and shoot digicams aren't, of course, the same ones that're used on 35mm film cameras. Digicam lenses have very short real focal lengths by 35mm standards, and proportionally smaller apertures to yield a given F-stop. This works out OK, because the lenses are made for the small sensors; if you only need to light up a fingernail-sized sensor, you don't need big glass to get good image brightness on that sensor. So although f8 on your digicam may give you the depth of field of f32-odd on a 35mm camera, it'll still give you the brightness of f8. Groovy.

And that's why, gentle and no doubt very bored reader, point and shoot digicams seldom let you set an F-stop higher than f8 or maybe f11. When f8 already behaves like f32, you don't need any more.

(If you've had enough of this subject, you'd better not go here. And definitely not here or here.)

Hey, you know what we need now? Even more confusion.

My EOS-D60 is a digital SLR. It looks fairly like a film camera, and takes normal Canon EF series lenses. But it doesn't have a full 35mm film sized sensor; thus far, full-sized sensors are still the domain of high end DSLRs which even I, despite my extraordinary panhandling skills, cannot afford.

The EOS-D60, like the later EOS-10D and EOS-300D, has a sensor about five-eighths of the width of 35mm film, and that gives it a 1.6X "focal length multiplier". A 100mm lens on a D60 behaves like a 160mm lens on a 35mm film camera. Good if you want telephoto, bad if you want wide angle, but at least it lets you hood the heck out of your lenses if you like.

This means the D60 exhibits the same F-number differences as point-and-shoot cameras do, only less so. Less field of view, more depth of field in a given photographic situation.

When I take a picture with my cheap 50mm lens at f1.8, my D60 writes in the file header that it was taken at 50mm and f1.8, and leaves me to remember about the multiplier. If I get a "full-frame" DSLR at some point and use the same lens on it, its file headers will say the same stuff but its field of view will be wider.