Digital camera shootout: Olympus C-2500L versus Sony DSC-F505

Review date: 17 January 2000.Last modified 03-Dec-2011.

It's now possible to buy digital cameras that can do almost anything a film camera can do, but don't come with giant battery packs and even bigger price tags. Digital is still a lot more expensive than film, but it is, arguably at least, no longer terrifyingly expensive.

Let's get the sordid little subject of price out of the way first, shall we?

The Olympus C-2500L has a recommended retail price of $2799 (Australian dollars), with discounters selling it closer to the $AU2500 mark. And it doesn't even come with everything you're going to need - of which more later. Figure on spending at least $2800 all told, even if you get a cheap one, and you won't be far wrong.

The Sony DSC-F505 is cheaper, but has similar hidden costs. With a base price of about $AU2100, it'll be about $2400 once you add a reasonable amount of memory and a spare battery.

Film photography aficionadoes may now present their monster list of all the regular photographic gear they could get for that kind of money. Top-of-the-line auto-everything SLR, really nice tripod, a couple of really nice lenses, a big old crate of film, and plenty of change for processing.

And yes, if you've got a place that'll put your film photos onto Kodak Photo CD, you'll get high-resolution (3072 by 2048!) digital images the equal of those created by any digital camera, with which you can still do all the digital fiddling you want.

Whether the advantages of digital - instant results, in-camera image reviewing, TV output, privacy - are enough to make up for the hefty price difference is up to you. But, for the sake of argument, let's say that the price tag doesn't send you screaming out the door, and you do want one of these cameras. Which one should it be?

First glance

It doesn't take a photographic expert to see that these two cameras are quite different creatures. The Olympus is much the same shape as a conventional Single-Lens Reflex (SLR) 35mm film camera, while the Sony - well, it wouldn't look out of place strapped to the side of Robocop's head.

Sony is better known for video cameras than for still cameras, and the DSC-F505 is, in many respects, like a video camera shot with a transmogrification ray. It's got exposure modes that work like a video camera, it gives you high-frame-rate previews on its screen like a video camera. And it can in fact record video, in a rather limited way, as I'll explain below.

The extraordinary design of the Sony makes its excellent Carl Zeiss 5X zoom lens the centre of the package. You hold the lens barrel in your left hand; that's where most of the camera's weight is. You just steady the camera, and work controls, with your right. It feels like no other camera ever made (there are other swivel-type digicams, but none with a lens like this!), but it's easy enough to get used to it. The DSC-F505's maximum image resolution is a highly respectable 1600 by 1200 pixels.

Olympus, in contrast, is primarily an optical equipment company, not an electronic equipment one. Its film cameras are well respected, and its digicams are carrying on the company tradition.

The C-2500L is a true SLR, with a viewfinder that looks through the lens. It's got a lot more "professional" features than the Sony, but it's not a lot harder to use. Its maximum image resolution is a slightly higher 1712 by 1368.

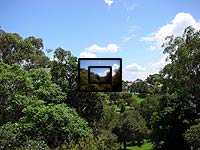

Comparative C-2500L (left) and DSC-F505 (right) image sizes

The Sony has no optical viewfinder at all - the only way to see what the lens sees is to look at the screen on the back, which is the only display the camera has. To make it easy to see the screen, the whole rear section of the camera pivots through a total of 140 degrees. This means you can use it like one of those camcorders with a pop-out swivel screen; you can hold it low and look straight down into it, or hold it high and peer upwards, or just tilt the screen as you like to suit whatever camera position's needed. Since the LCD screen, like all LCD screens, has a fairly narrow viewing angle, this feature is pretty much essential. It works very well.

There are a lot more differences between these two cameras, which I'll go into in a moment, but they have one big point of similarity. They both, generally speaking, take really good pictures. In pretty much any normal photographic situation, you can point either of these cameras at something and press the shutter button and be quite confident that you've got the photo you wanted to get, provided at least that you held the camera steady. With the LCD screens on both cameras, it is of course also easy to tell immediately afterwards whether you did in fact get the shot.

Size

Both of these cameras are quite petite. Looking at the pictures you might think they had heft equivalent to that of a serious 35mm SLR, but they're actually only medium sized units, and very easy to handle.

Neither is very heavy, either. The C-2500L tips the scales at about 470 grams (16.5 ounces) without batteries or memory cards, and weighs about 530 grams (18.7 ounces) ready to shoot. The Sony weighs a bit less - 435 grams (15 oz) empty, 475 grams (1 pound) ready to go.

The C-2500's weight is kept down by its magnesium alloy frame; the metallic looking panels you see on the outside of the camera, though, are all plastic. This doesn't make it feel cheap, exactly, but I can't honestly say it feels like a $2500 camera, either.

I originally thought the Sony also gave you plastic faux-metal panels over a sturdy frame, but then I realised that all of its body panels are actually a weird magnesium alloy that's, I suppose, just thin enough that it feels more like plastic, warming up rapidly in your hand. The Sony feels a bit more solid, overall, than the Olympus. As you'd want it to, given its variable-geometry design - the all-important swivel joint feels pleasingly robust.

Image quality

Enough about the feel of the things - what about the pictures?

Well, here some are.

The Olympus picture's on the left, the Sony on the right. The lighting was changing constantly on this half-overcast

afternoon so the Bridge and environs weren't quite the same colour for the two pictures. Both cameras capture admirable

detail - click the images for a low-compression excerpt.

The Sony excerpt looks noticeably sharper than the Olympus one, because its standard in-camera sharpening cannot

be disabled, whereas the Olympus' sharpening can, and was. See here for more on the sharpening

issue.

Overall, the Olympus takes better pictures than the Sony. To understand why, you need to understand compression.

The JPEG image format used by both of these cameras employs "lossy compression", which makes images much, much smaller than they'd otherwise be by throwing away a configurable amount of image data (find out more about lossy compression and image formats at my guide, here).

With lossy compression, raising the compression setting lets you fit more pictures onto a given memory card. But they won't look as good.

To get around this basic dichotomy, the best digital cameras offer a range of compression settings and resolutions. If you want to take a zillion happy snaps at a party, use low res and high compression. For that still life you plan to exhibit to your notoriously critical and short-tempered President For Life, use maximum resolution and minimum compression.

Realistically, quite high compression levels are acceptable for the vast majority of photos. If you zoom in, you can see the odd artefacts that appear in areas of solid colour and along edges, but quite a lot of "data reduction" can pass unnoticed if you don't magnify the image.

Sony like compression. They used a lot of it in their floppy-disk-based Mavica cameras. To fit a decent number of images on a floppy, the Mavicas compress the heck out of them. They make rather crunchy, ugly images. But people still buy them, because the images they make are good enough for a lot of purposes, and you can't beat the near-zero price of floppy disks for image storage.

Now, the DSC-F505 doesn't use anything like the amount of compression the floppy-cams do, but it's still on the high side for a semi-pro camera. Sony have clearly carefully evaluated the exact amount of compression they can get away with without it being glaringly obvious, on any images, without magnifying the picture.

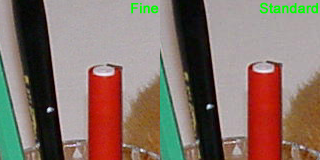

Sony image quality comparison.

This is a PNG image; only more recent browsers can display them.

The Sony has two compression modes, Fine and Standard, and three resolutions - 640 by 480, 1024 by 768 and 1600 by 1200.

The six image modes this gives you allow considerable flexibility, but the Olympus does better.

The Olympus has three image quality levels - Standard Quality (SQ), High Quality (HQ) and Super High Quality (SHQ). It really has four, though, because SHQ can either be 2.3:1 compression JPEG, giving files about 1.6 megabytes in size, or uncompressed TIFF format, creating monstrous 6.7 megabyte images.

SQ images are all 8:1 compressed JPEGs, and can be either 640 by 512 or 1280 by 1024 pixels in size. HQ images are also 8:1 compressed, but they're 1712 by 1368 pixels, the same resolution as SHQ.

When saving TIFFs, the C-2500L creates uncompressed, Macintosh-byte-order files. The byte order is no big deal, as any decent imaging package on PC or Mac can at least read and probably write both PC and Mac orders. The fact that they're uncompressed, though, is annoying.

TIFF compression, unlike JFIF compression, is lossless; the compressed version of a TIFF image is pixel-for-pixel identical to the uncompressed version. But it's significantly smaller - about 60% of the size of the uncompressed image, more or less. Compressed TIFFs take longer to save and load, unless you're using unusually slow storage media (like a floppy disk, for instance, not like a digital camera memory card), but the space saving has to be worth it when you're paying $US3 per megabyte (of which more in a moment). Only particularly old and crusty imaging software can't deal with compressed TIFFs, so it would have been nice if the Olympus could make them.

The Olympus' SHQ mode JPEGs are about 1.6 megabytes in size, and visually very hard to pick from its uncompressed TIFF images.

Both stand up to enlargement and processing better than anything the Sony can make; if you're just printing standard-sized photo images, though, you'd be hard pressed to tell the difference.

The Sony's "Fine" compression seems to be roughly the equal, file-size-wise, of the Olympus' Standard Quality mode. The Olympus is saving more pixels, though, and still seems to deliver slightly better results:

Sony Fine quality versus Olympus HQ quality. The higher Olympus resolution makes its 160 by 160 pixel excerpt

more highly magnified.

This is a PNG image; only more recent browsers can display them.

The Olympus can get away with using less compression, because it's got a lot more storage capacity than the Sony.

Storage

One of the C-2500L's most interesting features is its dual memory card slots. It can accept both the popular CompactFlash and ultra-slimline SSFDC (Solid State Floppy Disk Card, or "SmartMedia") memory cards (you can find out more about these formats at the CompactFlash Association and SSFDC Forum). Previous Olympus cameras were SSFDC only, which was annoying for many users; CompactFlash is not technically superior to SSFDC, or very much cheaper, but it's been around for longer and can be had in larger sizes.

From left to right: SSFDC, CompactFlash and Memory Stick

SSFDC cards top out, at the time of writing, at 64Mb (the 64Mb cards are still quite new, and rather more expensive than two 32Mb cards), while 128Mb CompactFlash cards are easily available and 160Mb ones are hitting the market.

The C-2500L comes with an 8Mb SSFDC card, which you might as well hang on to, but you'll need to supplement it with a CompactFlash card if you want to store a decent number of pictures.

You can only use Type 1 CompactFlash cards in the C-2500L, which rules out the fatter Type 2 cards, including IBM's 170Mb and 340Mb Microdrives. Microdrives are actual real live hard drives in a CompactFlash form factor. The 340Mb Microdrives are presently selling for less than $US500, making them substantially better value for serious digicam storage than Flash RAM-based cards. The 170Mb version is less than $US400.

Then again, if you drop a RAM card six feet onto a tiled floor, it'll very probably be just fine. You really, really don't want to do that with your jewel-like little Microdrive.

If a mere 240 or so HQ images is enough for you, a single 128Mb CompactFlash (or a couple of 64s) should do you just fine. Most people will be perfectly happy with a 32Mb card on top of the stock 8Mb.

All three memory card formats presently sell for something like $US3 per megabyte. For comparison, floppy disks are around $US0.20 per megabyte, and 3.5 inch hard disk storage is a tenth as much - or less.

The C-2500L's twin card system works very simply - there's a "SM/CF" button on the back of the camera, and pressing it instantly changes the card you're using. You can't automatically switch when you fill one card, and you can't split files across cards, but the system works fine as it is.

The C-2500L lets you copy images from one card to the other if you like, so if you have a card reader for your computer that only handles one format you won't be stuck serial-transferring images on the other card.

Sony Memory Stick and battery bay

The Sony camera, unsurprisingly, uses Sony's own "Memory Stick" cards (see Sony's page about Memory Stick here). Memory Stick's got a few special features - the cards have a write protect tab like a floppy disk's, for instance, and their connector design is more robust than SSFDC or CompactFlash - but they're not glaringly better, technically, than the other two options.

Memory Stick is an even younger format than SSFDC, but it still presently tops out at a respectable 64Mb capacity, with larger Sticks to come. Good luck finding a 64Mb Memory Stick in Australia at the moment, though. Wherever you buy your DSC-F505 will probably be able to kit you out with adequate memory, but may charge entertainingly high prices, and may only have lower capacity Sticks. The Stick that comes with the DSC-F505 is a miserable 4Mb, so you will need at least one more.

Nobody but Sony presently makes Memory Sticks, but their early price premium seems to have evaporated. All but the new and shiny 64Mb Sticks can now be had, from online dealers at least, at the same price as CompactFlash or SmartMedia - or cheaper. You'll be wanting at least one or two extra 16Mb cards with your F505; the stock 4Mb card isn't much use, so if you can trade it in on a bigger one, do.

Moving data

When it comes to getting your pictures from the camera to a computer, the Sony's the clear winner. It supports USB data transfer, and the Olympus doesn't.

DSC-F505 USB and serial connectors.

Digital cameras are exactly the kind of gadget that USB was created to work with. They generate medium-large amounts of data, so you want a decent transfer rate, but you also want to be able to plug the camera into the computer, not reboot, move the pictures over, unplug, not reboot, and go.

USB makes this possible; it's hot-pluggable, so devices can be added and removed on the fly. And it's acceptably fast, and USB-compatible cameras can appear, to the computer, just like a removable media drive. This is exactly how the Sony works.

Because the Sony can be used like a system drive, you can copy files not only from but also to its memory card. But you won't be able to view an imported image unless it's originally been made by the camera, and is named correctly (dscxxxxx.jpg, where xxxxx is five digits). It'd be cute if you could load up the camera with images from your collection or business presentation slides or something and use its video out to show them via the TV or projector of your choice, but it's only possible if the images originally came from the camera, and you haven't changed them at all.

The only problem with USB data transfer is that only relatively recent computers and operating systems support it. In the Windows world, as I write this, Windows 98 is pretty much your only option. Late versions of Windows 95 work with USB, but Win98 has it all built in and set up from the get-go. All you need is a computer that has USB ports on its motherboard - which they all have had, for a while now - or a USB port card for your older PC, which will only set you back about $AU70.

If you've got a USB-equipped Macintosh, things are just as simple.

But, if you want USB, you don't want the Olympus. There are cameras selling for less than half its price that have a USB interface, but Olympus didn't put one on the C-2500L.

There are four alternatives to USB data transfer. One, used by high-end cameras, is a SCSI (Small Computer Systems Interface) interface. SCSI is really fast, but it's not hot-pluggable, and not many computers come with a SCSI interface as standard. The other three alternatives are serial transfer, a separate memory card reader, or a floppy disk adaptor - SSFDC cards can be plugged into adaptors and read by normal PC floppy drives, with a special driver. You can also get PCMCIA card adapters for Memory Sticks, so you can read them in laptops or any other PCMCIA reader.

The C-2500L serial port (grey, bottom), video out (yellow, top) and power jack (in use).

Serial is simple enough - hook the camera up to the computer's serial port, run a special data transfer utility on the computer, and move the data. Every PC and Mac that ever there was has a serial port or two, so you don't need a recent machine with USB, but the down side is that you do need that special software, and the data transfer rate is pathetic. Of which more in a moment. The Olympus supports serial, and so does the Sony - but you'll only have to use serial with the Sony if the PC you're connecting to doesn't have USB.

A separate card reader lets you take the memory card out of a camera and plug it into your PC. Older low-cost external readers connect to an IBM-compatible computer's parallel port, and are quite fast when they work properly. But, like many parallel-connected devices, they commonly don't. Current external readers use USB. Cheap internal card readers - which mount in a 3.5 inch drive bay - use the ATA (IDE) interface included in all PCs and recent Macintoshes, and more expensive internal and external models use SCSI. You can get a USB external card reader for less than $US50, and you can get them in Australia now for $AU130 or so.

So what if you're stuck with serial? It works, all right, but it's slow, slow, slow. HQ pictures from the C-2500L run to about half a megabyte each, and the fastest serial port speed you're likely to be able to use is 115,200 bits (not bytes) per second.

If you want to transfer, say, 36 of these half-megabyte shots, you'll be waiting for half an hour. This compares very favourably with how long it'll take you to get a 36-shot roll of film developed, of course. And because the images transfer over one after the other you can be looking at and working with the early shots while the late ones are still percolating through. But it's still not quite the instant gratification digicams are supposed to bring.

Incidentally, if you avail yourself of one of the 128Mb CompactFlash cards currently available, you'll be waiting a good three and a half hours to serial-transfer its entire contents.

On the other hand, the Sony camera's USB interface shifts a bit more than a megabyte every four seconds. It's about 25 times faster than the Olympus - or than its own serial transfers.

To add insult to injury, the Olympus serial transfer software ain't too great. It doesn't remember the directory you want to put pictures in, and it can't automatically delete images from the camera on download.

Furthermore, if you're running the Olympus software under Windows 95/98 (as opposed to Windows NT or Windows 2000 Professional or Server), it seems to suck down more than 90% of your CPU time, whether it's actually doing something or not. This means it causes about as much system slowdown just sitting there doing nothing as Photoshop does when it's flogging hard at applying a complex effect to a huge image. Given the lengthy periods for which people without a card reader are likely to have to run this software, this strange system load is quite annoying.

The Sony software, PictureGear Lite, is nothing very special either for the basic task of transferring images via serial. PictureGear lets you see thumbnails of the pictures and drag-and-drop them using a standard Explorer interface, but when it's actually performing the transfer it doesn't play well with other programs. Most stuff works, but anything that tries to minimise PictureGear seems to paralyse the computer. And the transfer completion window only shows the completion state of the current file, and sometimes gets stuck on the screen after transferring the last one. And you can't delete images after you transfer them.

Of course, you'll only have to put up with all this if you don't have USB or a card reader.

If all a camera supports is serial, and you want to move reasonable numbers of pictures fairly often, a card reader is the only way to go. If the camera supports USB, though, it can effectively behave as a card reader all by itself.

Battery life

Digicams eat batteries a lot faster than film cameras. Exactly how much faster they eat batteries has been a serious embarrassment to the digicam industry for years - not only are digicams way more expensive, but they make you kit yourself out with a bandolier of AA cells.

Fortunately, things have been slowly improving. No great advances have been made in the power consumption of digital cameras - better technology has given us cameras that work much better, but draw about the same juice. But some progress is being made in battery technology, with high-capacity rechargeables becoming commonly available.

Old-fashioned 600 milliamp-hour (mAh) AA nickel-cadmium (NiCd) cells are a waste of time for digicams, but you can now buy NiCd and, more recently, nickel metal hydride (NiMH) cells with capacities of well over an amp-hour (Ah; 1000mAh) for reasonable prices. The Olympus comes with four NiMH cells rated at a honking 1450mAh, and a charger; the DSC-F505 uses one of Sony's own "InfoLithium" lithium-ion battery packs.

I hooked up my multimeter to the C-2500L and took some readings. Just sitting there, turned on but doing nothing, it draws about 230mA from the 4.8 volts its four NiMH cells deliver. Use the zoom drive and you draw 560mA; pop open the flash and it'll draw around an amp for a couple of seconds as it charges. If the camera has to use its autofocus illuminator (more on this later), it needs 1.2A while it's shining; when locked on and ready to take a picture, with its screen displaying the image settings, the camera draws a bit more than an amp.

Right after taking a flash picture it draws maybe 1.8A for a moment as it saves the picture and charges the flash, but that drops to about 750mA after the flash has charged. Reviewing images draws about 740mA, and a bit more when you're changing the picture you're viewing.

Pleasingly, the amount of current drawn when the Olympus is transferring files over a serial cable is no higher than the quiescent 230mA or so.

This quiescent current draw will flatten a set of 1400mAh NiMH cells in about six hours, by itself. This assumes the camera stays powered up all that time, which it won't; the default auto-power-off interval is only 60 seconds (you can change it to 2, 5 or 10 minutes, or disable auto-off completely).

How much juice does taking one picture consume? Well, let's presume that you use the motor zoom for a couple of seconds and point the camera at the target with the screen active for about five seconds, with the whole picture-taking-and-saving sequence taking about 12 seconds. Tally up the current consumed and the time taken, and you get about 13 amp-seconds, which is about 3.6 milliamp-hours. If 3.6mAh is consumed every 12 seconds - in other words, if you take flash pictures continuously without a break - a set of fully charged 1400mAh NiMH cells will be flat in about 80 minutes. But you will have taken almost 390 pictures!

In real use, pictures generally take rather longer than this to take, with false starts and reframings. The constant fifth of an amp drawn while the camera's just sitting there turned on, and the various menu accesses, zoom uses and focus attempts without pictures taken mean that 150 pictures, at most, is what you're likely to manage in a serious session from one set of batteries. You'll get less than two hours of total run time. You can eke out the batteries by turning off the image review after taking a picture, and the status display when the camera's ready to shoot.

So what's the Sony's current draw, in comparison?

Well, I'm not sure. I chickened out.

The DSC-F505 battery-charger-cum-AC-adaptor is, basically, a video camera battery charger, and like many video camera chargers it can either charge a battery or power the camera, not both. You wouldn't think it'd bust Sony to make a slightly beefier unit that could handle both tasks at once, but there you go.

Plugging the DSC-F505 into the AC adaptor is very simple - there's a lead that plugs into the charger module and terminates in a dummy battery. Pop the dummy battery into the battery compartment, hinge out a little rubber cover on the compartment door for the cable, close the door and you're in business. The advantage of this design is that it's impossible for the AC adaptor plug to accidentally fall out of the socket, as can happen to the C-2500L and pretty much every other digicam. The disadvantage is that you can't just buy a cheap off-the-shelf AC adaptor to power the camera, for instance while you charge a battery. If the dummy battery setup does nothing with the third conductor (used for data communication to InfoLithium batteries) then it'd be easy to hack a big battery pack or suitable cheap plugpack onto it, but I don't know whether something mystic is going on there or not.

I could have carved up the Sony's special three-wire AC adaptor lead and done some measurements, but that probably would have made the people who gave me the camera angry.

The total power consumption of the Sony, though, seems to be similar to that of the Olympus. Its tiny NP-FS11 InfoLithium battery pack is only a 3.6 volt unit, with a "4.1 watt-hour" rating, which translates to about 1.14 amp-hours. The 4.8V combined potential of the four NiMH AAs in the Olympus, and their higher amp-hour rating, means the Olympus cells carry around about 60% more energy than the Sony pack - they should be good for about 6.7 watt-hours. The ones I got with the review camera seemed to have had a rather hard life already, and might have been down a bit on their rated capacity.

(Incidentally, my monster five cell 7Ah pack scores 42 watt-hours, though it'd be more like 34 in real life, since digicams don't draw much less current from higher voltage.)

The big deal about InfoLithium is that devices that use these batteries can tell you accurately how much power they have left. This isn't just a sales gimmick; it's really true. The DSC-F505 keeps a running update of the time remaining in the top left corner of the display.

The InfoLithium system isn't psychic - if you change how you're using the camera, the remaining-time display changes too - but it genuinely does give you a decent warning of an impending flat battery.

Which is more than I can say for the Olympus. Like many AA-powered devices, this one seems to have a battery level meter calibrated more for alkalines than for rechargeables. Alkaline AAs are poorly suited to high-draw devices like digicams, but that doesn't matter; the discharge meter seems to be made for them. The much more precipitous discharge curve of NiMH and, especially, NiCd cells means you'll get very little warning of flat batteries, and you may also have to deal with false alarms - your cells may, if they're getting on a bit and have been roughly charged, develop voltage depression and still be able to run the camera for quite a while after their terminal voltage indicates to the camera that they're about to die.

The InfoLithium pack powers the Sony for, roughly, 60 to 80 minutes, depending on how many flash pictures you take, whether the backlight's on and so on. So we're talking, generally speaking, maybe two-thirds of the run time you get from a set of good NiMH AAs in the Olympus. Since it's got two-thirds the power in that little battery pack, this indicates a somewhat more frugal design - remember, the Sony's screen is on all the time.

Overall, given the nifty power meter, InfoLithium's a lot better. Then again, it's a lot more expensive. The NP-FS11 pack's list price is $US60, with discounters selling it for a little less. In Australia, you're looking at $AU90 at least, and probably $AU100 (or more, given the cheerfully audacious accessory pricing policies of some camera stores). You'll probably want at least one spare battery if you buy a DSC-F505, so this is a significant hidden cost.

In contrast, a set of four 1.3Ah NiMH cells, roughly as good as the ones the Olympus comes with, will cost you little more than $AU20. On a dollar-for-dollar basis, the Olympus gives you a lot more run time. And, in a pinch, you can always purchase some unsuspecting alkalines and drop them into the C-2500L. Sure, the poor things will be whipped to death in half an hour or so, but at least you'll be taking pictures, which is more than the guy who's run out of charged InfoLithiums is going to be doing.

From flat, the InfoLithium charger takes a bit less than two hours to mostly charge the Sony's pack. I say mostly because that's when the charge light goes out, but the charger will actually be topping off the pack for another hour, and you'll have to wait that long if you want to get maximum capacity.

The AA charger included with the C-2500L is a decent unit. It can charge any number of cells up to four, and it takes about three hours to fill 1.4Ah cells from flat. But it's handicapped somewhat by the touchy nature of NiMH cells. You can tell when NiCd cells are fully charged because their voltage drops, by just a few hundredths of a volt at first, as they go into overcharge. NiMH doesn't have a voltage drop - its voltage rise just slows down and eventually the cell voltage levels out. This is rather harder to spot. As a result, the chargers are more sensitive, and can "false peak" cells (finishing the charge too early), especially if the cells are warm and freshly discharged.

The Sony InfoLithium pack seems as clever about charging as it is about discharging; there wasn't a sign of false peaking or any other such problems.

Broadly speaking, there's no glaring difference in the run times of these two cameras. Neither eats batteries like jelly beans, like early digicams (though you'd still get, at best, half an hour out of a set of alkalines - see my page here to find out why, and to find out how to make bigger packs), but you still have to resign yourself to video-camera-esque battery life, not film camera duration.

If it is possible to hack the Sony's power lead easily, it could be worth doing if you need long run times on the cheap. Three 5Ah NiCd cells, enough to match the 3.6V of the InfoLithium pack, would cost you about half as much as another InfoLithium but give more than four times the run time - maybe even five times. You'd lose remaining-time monitoring, but if the fully charged remaining time was four or five hours, would you care? Even if you bought a basic charger along with the cells, the whole shebang would still only cost you about as much as one InfoLithium battery!

The C-2500L's four 1450mAh NiMH cells and the Sony's tiny InfoLithium pack, perched on top of my boat-anchor five cell 7Ah NiCd pack (which was powering the Olympus when it took this picture!). The InfoLithium pack only takes up about as much room as two AA cells, but it contains 20% more energy. Then again, it costs about ten times as much as two decent AA NiMH cells.

The huge NiCd pack (made of F-size cells, incidentally; read more about making your own battery packs here) contains about ten times the energy of the InfoLithium pack, and about 6.3 times the energy of the four AAs. I treat it, essentially, as a mains adaptor which just happens not to need to be plugged into the mains. Every now and then I charge it. I practically never run it flat.

Viewfinders

The Sony has no optical viewfinder; it uses its screen for everything. The Olympus takes the opposite tack; you can't use its screen to preview at all, but have to use the through-the-lens (TTL) viewfinder. The screen does have a function when you're about to take a shot; it can display the settings the camera's using once you've half-depressed the shutter button. If you want to save the batteries, you can turn this display off. You can also turn off the normal display of just-taken photos, or, in a nice touch, set the camera to automatically display them for a full five seconds, regardless of how long the image actually takes to save.

The Olympus viewfinder has a dioptre adjustment wheel on its side, so you can wind the focus in and out to accommodate different eyes, but it can still be a bit awkward when you're doing super-close macro work (of which more later).

Both the Olympus camera's viewfinder and the Sony's LCD screen show a significantly smaller area than the camera actually photographs. This is behaviour they share with many cameras; the idea is to minimise severed heads and similar framing disasters by giving the customer more than he expects. It's usually described as a "95% view", because that's how much of the real captured frame you can see through the viewfinder. A 95% view also allows for camera movement in hand-held shooting.

On lesser digicams, with less resolution to play with, accurate framing information is very important. The more of the frame you manage to fill with the subject, the better the final shot will look. This is less of a concern with higher resolution cameras like these; you can crop down a little to get rid of the unexpected extra area around the section the viewfinder showed you and still have lots of pixels for a nice sharp image.

Displays

The C-2500L sports a 1.8 inch 122,000 pixel colour LCD on its back panel, with controls surrounding it on two sides.

It also has a supplementary conventional black and white LCD on the top of the camera, which shows the basic settings currently chosen and means the big panel needn't be on all the time.

Sony screen swivel - 140 degrees of rotation!

The Sony has only one display, a two inch colour LCD panel. It's significantly larger than the C-2500L's screen, and the swivel mount makes it easier to view, but it has only slightly higher resolution.

No LCD screen yet made does a perfect job in full sunlight, but the DSC-550's does quite well. It's a reflective design, which prevents it from washing out completely in sunlight. A simple switch under the screen disables the backlight; the backlight makes no difference to the look of the screen in sunlight, but uses up battery power you might as well save.

The Olympus camera's LCD isn't as good as the Sony's in full sunlight, but it doesn't need to be; you've got a proper viewfinder for composing your pictures. Neither camera's screen gives you any real idea of what a picture looks like if you're standing in full sun, but both work fine for menus. If you step into the shade, reviewing pictures with either camera is possible, but you really can't pick whether you've got the exposure right. Both LCDs are streets ahead of the crummy screens on older digicams, which were close to useless in sunlight.

Both cameras have a good selection of hardware buttons for commonly chosen features, but both also lean quite heavily on their menu system for more elaborate functions. Of the two menu systems, the Sony's is better. Its little Game Boy-esque four way joypad button can be pushed in to select an option; the Olympus has a somewhat less comfortable four-way button with a separate OK button. The Sony's menu layout manages to be straightforward without becoming a big pain to use as you become experienced with it.

The Olympus uses a traditional paged menu system, which also works fine. It's got more settable options than the Sony, so its menus are necessarily more complex, but it's only marginally harder to use overall.

Neither camera has any real ergonomic or user interface problems. Earlier Olympus cameras put the power button too close to the shutter button, but the C-2500L puts it in the middle of the mode selector ring on the back, out of harm's way. And some basically box-shaped digicams seem specially designed to make the operators nose rub all over the LCD panel; neither of these cameras has that problem.

That said, the Sony makes the Olympus camera feel... well, unsexy. Quite apart from its avante-garde look, there are lots of little touches about the DSC-F505 that make it more pleasing to use. The way the battery/memory card door springs open at the flick of a latch and clicks shut just as easily, for instance. The Olympus battery door pops open easily enough, but you'll need both hands to close it. This is probably because the battery terminal springs are extra-springy, to deal with the slightly short rechargeables many people use.

The Sony has a very easy to use slide-and-flip cover over the data ports on the top; the Olympus uses a plastic door retained with a rubber hinge, which feels flimsy and gives the impression that it was added as an afterthought. The oily smoothness of the Sony's manual focus ring (of which more shortly) beats the heck out of the button-clicking you have to do to manually focus the C-2500L. The Sony's four-way-and-click control pad feels better than the Olympus attempt, too.

Both cameras make you go to the menus for functions that you might prefer to see on a button, but the Sony has more nice touches to make up for it, like the ability to press left on the joypad when you're in picture-taking mode and see the last shot taken, with the option to delete it.

The Olympus feels like a 35mm SLR that's had a major hot-rodding job done on it; the Sony feels like a purpose built new kind of animal.

This is not, however, to say that the difference is night and day. The Olympus is a very nice camera to use, as well, and there's nothing terribly wrong with the 35mm SLR shape it adopts. It's just not necessary for a digital camera to be the shape of a film one, and the Sony takes advantage of this fact. No film camera could be the DSC-F505's shape, let alone have its articulated hand-grip.

Flash

Both cameras have a pop-up flash mounted over the lens barrel, manually released with a button on the Olympus (right picture, above) and a slide catch on the Sony (left picture). Both flashes are more than adequate for most pictures. But neither has the magical powers most people appear to expect, at least if the number of flash-bulbs that always seem to be going off during fireworks displays is any indication.

As usual, both cameras let you set the flash to go off when the camera needs more illumination, or to go off every time ("fill" flash). But, beyond this, the Olympus flash is the clear winner.

The only flash settings the Sony offers are three "level" options, which let you choke back the flash a bit if it's tending to overexpose, or pump it up a little. And the Sony has no shoe for a secondary flash. You could use a slave flash with it - slave flashes go off when their light sensor detects another flash firing - but then you'd have to manually change the slave's settings to get the exposure right, and put up with always using the built-in flash as well, to trigger the slave.

The Olympus flash setup, by comparison, has everything that opens and shuts. Most useful for happy snaps is red-eye reduction mode, where a sequence of pre-flashes fires before the picture's taken to contract the victim's pupils and prevent them from looking any more like the Spawn of the Dark Lord than they do in real life. The Olympus also lets you set the flash to first or second curtain mode (flash at the start or the end of the exposure). There's also flash power adjustment, like the Sony's, though it seems less necessary; the Sony seems a bit more prone to overexpose flash pictures than the Olympus.

And the C-2500L has a hot shoe for an extension flash. If you use the Olympus FL-40 flash with the C-2500L, the extension flash integrates with the built-in one and sets its energy appropriately for the chosen camera settings. You can also use both the built-in and extension flash at once, and angle the extension flash, if you like, to reflect off a wall or the ceiling to reduce harsh shadows. The FL-40 can even be told that you're using the standard Olympus telephoto or wide angle screw-on lenses, and adjust its settings appropriately.

Zoom

DSC-F505 optical zoom (digital zoom not used).

The Sony's big Zeiss lens has an unusually high 5X zoom capability, with another 2X digital zoom on top of that for 10X total. The digital zoom, like all digital zooms, just makes small blocky things bigger and fuzzier. But it's still handy to help you get the framing right on distant targets. There's a line in the zoom indicator on the display that shows you when you've used up the real zoom, and you can disable digital zoom completely as well, so it's no problem.

The only real problem with the Sony's zoom capability is that 5X can be a bit too telescopic for effective hand-holding of the camera! You don't have to have very quivery limbs for a 5X-zoomed picture to come out a bit blurred, and for best results a tripod, or at least something solid to rest the camera on, is a good idea.

C-2500L zoom.

The C-2500L loses to the Sony in the zoom department; it has the same anaemic 3X zoom as many other digicams. Except, of course, for those that have only 2X, or none at all.

Both cameras use a two-way control to set zoom - a slide switch on the Sony's top rear edge, and a rotating lever-dial arrangement around the Olympus' shutter button. The Olympus zoom only has one speed, which makes it annoying to make fine framing adjustments. Of course, with lots and lots of resolution, fine framing adjustments aren't that important, and the SLR viewfinder lets you instantly see the results of your zoom changes.

The Sony zoom has smoothly variable speed, but it's let down by the refresh rate of the LCD display. While the LCD updates respectably quickly, it's still a long way from the 25 or so frames per second needed for truly smooth video. As a result, you don't get instant feedback of the current zoom position, and it's easy to overshoot. The zoom itself doesn't lag behind your input, but the display of the result does, which is just as bad. This problem doesn't exist, of course, in cameras like the Olympus that have an optical viewfinder.

Remote control

A standard feature with the C-2500L in Europe and the US, but originally a $AU75 option here in Australia (after I wrote this review, it became a standard item), is an infra-red remote control - the same RM1 remote that comes with lesser Olympus digicams. There's a receiver on the front of the camera under the shutter button.

The dark patch beneath the shutter button and zoom control is the IR receiver.

The remote has roughly the footprint of a matchbox but is half as tall. You can use it to zoom in and out and trip the shutter, in plain record mode. This lets you use it like a cable release, for vibration-free tripod pictures.

In playback mode the remote lets you move from picture to picture and zoom in and out, including zooming out to the thumbnail display. The playback control is, of course, of no particular interest unless you've got the camera hooked up to something via its TV output (see below).

The Sony, like pretty much all other cameras, has no remote. This is a bit odd, really, as a remote control would totally suit the DSC-F505's video-camera-ish feel.

Macro mode

Olympus macro shot on the left, Sony on the right.

Macrophotography is any photography that produces an image on the film (or CCD) larger than the original subject, without using a microscope. Of necessity, this means taking pictures of things pretty close to the camera, and sometimes very close indeed, if the lens you're using can't do macro work when it's zoomed in.

In practice, "macro" is just used to refer to any extreme close-up, regardless of whether it technically constitutes creation of a larger-than-life image inside the camera. Given the small size of the image sensor in consumer digicams, almost all "macro" shots taken with them don't, technically, qualify. But no matter.

The DSC-F505 has a very good macro mode. It can focus, in zoomed-out mode, on objects as close as four inches. The picture at right, above, is about as close as it can reasonably get.

(click for full-scale excerpt)

The Olympus, though, blows it into the weeds.

The C-2500L has two macro modes. The first works from 12 to 24 inches, but the "Super Macro" mode works as close as 0.8 inches - a mere 20mm or so. It's not capable of taking a sharp picture of a bug walking across the lens, but it gets darned close.

Super Macro can focus tightly enough that the chief problem in taking ultra-close pictures becomes lighting the subject properly, and keeping the shadow of the lens off it.

Unfortunately, you have to focus this close to get maximum magnification. A truly excellent super-macro mode, such as that of Nikon's popular Coolpix 950, works when the camera's zoomed in a bit, so you can be further away from the target. Having to practically - or literally - rest the edge of the lens on the subject is a good party trick, but undesirable in practice.

The minimum macro field of view of the C-2500L is about 40 millimetres (1.5 inches) across. This is in the lens-on-the-subject mode; if you pull back you can zoom in a bit, but the camera's minimum focus distance moves out faster than the zoom brings the target in, so you end up doing worse than you would if you just jammed the camera next to the target at full wide angle.

Now, 40mm field width is pretty respectable, but the Coolpix 950 can do twice as well, if not even better. Given that the Coolpix can be had for not a lot more than half of the C-2500L's price, it's pretty clear where you should go if phenomenal macro capability is what you're after.

Flash shadows - Sony on the left, Olympus on the right.

There's another limitation to very close work - you can't use the flash. Since both cameras have a flash quite close to the lens, the flash will cast a shadow on the target if you're too close.

All that said, though, both of these cameras do a good job for macro work. Perfect they are not, but adequate they are. Compared with older, cheaper cameras like the Kodak DC-120 and DC-220 I talk about here, both of these cameras are a dream for close-in work.

CCDs

A Charge Coupled Device (CCD) image sensor is at the core of both of these digicams. The Sony has a standard 1/2 inch CCD behind its big lens, while the Olympus has a larger 2/3 inch model. A bigger CCD has room for more pixels at the same density.

The 1712 by 1368 resolution of the C-2500L makes it a "2.5 megapixel" camera; the actual number of pixels is only about 2.34 million, though. The Sony's 1600 by 1200 puts it in the "2 megapixel" category, with 1.92 million real pixels.

Sensitivity

The ISO sensitivity of both of these cameras is 100. This is definitely on the low side, compared with film, but low sensitivity is a problem shared by most digital cameras. When you've got low sensitivity, you have to use longer exposures and/or larger aperture settings to get the same image intensity, and it becomes impossible to get clear pictures of fast action in dim environments if the target isn't close enough for a flash photo.

The C-2500L tries to get around its limited sensitivity by letting you boost it, to 200 or 400. This is just a gimmick, though; it's artificially multiplying the values it gets from the CCD, and it multiplies the graininess right along with them. Yes, doubling the sensitivity lets you halve the shutter speed, and therefore take less blurry pictures of moving things. But the "faster" settings are considerably grainier; you don't get something for nothing.

Lenses

The C-2500L has a 36-110mm equivalent zoom lens, with exactly two possible aperture settings - the aperture is as open as it can get, or it's as closed as it can get. The F-stop you get from the two aperture settings varies with the amount of zoom you're using; when you're zoomed all the way out you've got F2.8 or F5.6, when you're zoomed all the way in you've got F3.9 to F7.8.

This restricted aperture could annoy photographic enthusiasts looking for true flexibility, but it's not as much of a limitation as it sounds. The Olympus has lots of possible shutter speed settings, so it doesn't need lots of aperture settings as well in order to get a decent range of possible exposures.

Assuming you're not short of shutter settings, the most common reason to manually change your aperture setting is because you're trying to restrict or expand the camera's depth of field - how deep its in-focus area is. A small aperture gives you greater depth of field, so backgrounds are sharper; a large aperture reduces the depth of field, giving the fuzzy background you often want for portrait photos.

In this situation, many photographers end up using the biggest and smallest settings of variable aperture lenses anyway, so Olympus seem to have decided that they might as well keep the price down by only offering two settings. When you decide to go with only two settings, they have to be two middle-of-the-range ones. It'd be no good if the camera offered a wide-open mode with practically no depth of field and a flyspeck-sized alternative that didn't let any light in. So this is what you get.

The C-2500L's available F-stops would be on the wide side for a 35mm camera, but the small image sensor in a digicam means a given F-stop delivers a tighter depth of field than it would in a 35mm.

Because of the moderate F-stop selection, if you want to tightly restrict or greatly extend the depth of field, the C-2500L isn't the camera for you.

The Sony is more flexible in the aperture department. When zoomed out all the way, the Sony offers F2.8; zoom in and the widest aperture you can pick is F3.4. But at any zoom level, you can also pick F4.0, 4.8, 5.6, 6.8 and 8.0. It's a little fiddly to do it, as you have to use the menu system, but at least you can.

All of those F-stops aren't quite as good as they sound, though. Thanks to the DSC-F505's low sensitivity, the higher F-stops are little use at night, or perhaps even indoors during the day for the top couple. The flash can provide more than enough illumination to get a decently bright picture at close range, but since you can't set both aperture and shutter speed, the camera may get its exposure disastrously wrong. Not to mention the fact that when the screen's dim, it's hard to focus manually. The end of the C-2500L lens has a 43mm thread on the end for filters and add-on lenses, many of which use a 43-to-46mm step-up ring, which Olympus include with their own add-on telephoto and wide angle lenses. You can also step the threads up to 55mm with an appropriate ring, and use a bunch of other lenses and filters - although step-up rings often cause the maximum wide-angle setting to have a bit of a black vignette around the edge. The Sony has a 55mm thread as standard, so larger filters and add-on lenses can be used without any adaptor rings.

A thread on the end of the lens is far from being a substitute for the proper interchangeable lenses of SLR film cameras. But it does let you add a bit more zoom or macro capability, or add a "hot mirror" infra-red filter to reduce the blue cast on outdoor shots caused by the both cameras' infra-red sensitivity.

Here's how you tell if your camera is sensitive to infra-red - take a picture of a remote control. The remote's IR LED doesn't emit anything visible to the naked eye, but digital camera CCDs pick it up just fine - in fact, they're more sensitive to it than to visible frequencies, which is why the LED shows up white. A "hot mirror" filter will block IR, may slightly improve outdoor shots, and will also protect your lens from damage.

Incidentally, film cameras have the opposite problem to digicams in this respect - they're sensitive to ultraviolet light. Accordingly, a lot of people put a UV filter on their camera for the same reasons listed above. Putting a UV filter on a digicam, though, won't make much difference to anything; CCDs have a hard enough time seeing violet light, let alone ultraviolet.

Olympus' page of screw-on lenses and adaptors that suit the C-2500L is here.

Below the C-2500L lens lurk a pair of startlingly high intensity amber LEDs, which are used to help its autofocus in dark areas. They work well, casting two overlapping circles of orange light to a rather impressive distance, but they're alarming if someone lines the camera up on you without your knowledge.

Both cameras come with clip-on lens caps that engage the threads on the end of the lens, and will work just as well on any screw-on extras that have a thread of the same size on their outer end.

Focus

Both cameras have ordinary optical autofocus - internal electronics look at the image coming through the lens and shift focus until an angled view through one side of the lens seems to coincide with a similar view through the other. When they're in autofocus mode, neither camera will let you take a picture if it doesn't think it's got a focus lock. The autofocus indicator - a green light beside the viewfinder on the Olympus, a green blob on the screen on the Sony - just flashes if the camera can't focus.

The Sony doesn't actually fail to lock very often at all, but it ought to do it more often. It's good at deciding it's in focus when it actually isn't. It seems, perhaps, to weight peripheral detail too high, so it can focus on the background rather than the foreground, or occasionally on nothing at all. Dim fuzzy scenes; the wall you just pressed the lens up against; the inside of the lens cap - the Sony will merrily photograph them all!

Here's a perfect example of the Sony camera's overoptimistic autofocus. It was sure it had the coin

in focus, in macro mode. Well, some of the wood-grain at the top of the frame was fairly sharp, but the coin is solid

fuzz, because this is well inside the DSC-F505's four inch macro limit.

You can avoid the more ludicrous mistakes by simply noticing that nothing worth photographing seems to be visible on the screen, but if the image seems OK on the screen you may waste time taking rubbish pictures.

The Olympus is much stricter about its focus locking; it very seldom mistakenly decides it has lock. The down side is that it occasionally fails to focus on a seemingly simple target, especially when you're using Super Macro mode.

The list of things both cameras have trouble with contains the usual suspects - things that glow, shiny things, fuzzy things, moving things. The Sony will often let you take a picture of these things, but it's doing you no favours, as the result is likely to suck.

On awkward targets, one option is to lock the focus on something else - half-press the shutter button while pointing the camera at something the same distance away as the real target, then re-aim the camera and taking the picture.

The Real Man's option, of course, is manual focus.

In the manual focus department, the Sony is the winner, because it has something close to true manual focus. There's an oily-smooth fly-by-wire focus ring (it's not mechanically connected to the focus mechanism, but controls it via an electronic encoder) at the end of the Sony's lens, and in manual focus mode you can twiddle it back and forth to hunt that elusive sharp picture.

The camera gives you an indication on the screen of how far out you've focussed, and which way it thinks you should go - but you can take a shot any time you like. You change modes with a switch on the lens barrel. It's a very pleasing system to use.

For manual focus, the Olympus is more like older consumer digicams - you pick possible focus distances by moving forward and backward through set distance options. It's harder to use than the Sony, but it's a little more featureful.

The FOCUS button beneath the Olympus' top display cycles through the two macro modes, infinity lock for landscape shots, and manual focus mode. You set the focus distance by moving the four-way button on the back of the camera up and down. There's also a "quick focus" mode; if you press the OK button while framing a shot, the focus locks to whatever distance you've specified in the setup menu.

There's no optical focus aid built into the C-2500L's viewfinder - you don't get a ground-glass focus spot or a rangefinding prism, for instance, as is provided by manual SLRs. There's just a plain black ring marking the middle-of-frame. The ring's great for seeing if you've set the dioptre adjustment at the side of the viewfinder correctly for your eyes, but that's all it does.

It's therefore tricky to tell when you've got manual focus just right, and "bracketing" your shots by taking a couple at different likely focus distances is a good idea for the very best results.

Multimedia

One of the Sony's big "wow!" features, which is not actually anything worth writing home about, is the ability to record sound and video.

Any excitement you may be feeling about this feature dissipates pretty quickly when you find out that the longest clip the DSC-F505 can record in 320 by 200 (its best resolution) is 15 seconds.

I don't know why this is, exactly. It's not a storage space issue.

The Sony can record MPEG clips in 320 by 200 or 160 by 112 pixel sizes. The bigger size only takes up around 1.3 megabytes for 15 seconds, and the smaller size takes up about the same amount for 60 seconds. You set a minimum time for the clip to run - 5, 10 or 15 seconds - but, if you're using the lower resolution, you can then just keep holding the button down and record up to a full minute.

320 by 200 video frame

160 by 112 video frame

Video frame sizes compared with 1600 by 1200 image

Sony have done this same trick with other cameras. Their older FD81 Mavica lets you capture up to 60 seconds of video to a floppy. Perhaps the DSC-F505 is also tuned to make floppy-compatible files, though it of course doesn't need to be.

You could fit almost 12 minutes of 160 by 112 video onto a 16Mb Memory Stick. If they'd let you. Sure, the image quality sucks in 160 by 112 and isn't a ton better in 320 by 200, but as a "freebie" feature, it'd be a good one.

Having a setting for the movie clip capture that automatically cuts off recording before the file gets too big for a floppy might be quite handy, but it'd be even better if you could record continuously to the Memory Stick for as long as you liked, or until you ran out of storage. Even a 4Mb Stick would therefore be good for about three minutes of low-res video.

The frame rate of the movie files seems to be locked at 25fps, but the actual number of different frames per second (they repeat, which is fine in the MPEG format and wastes no space) is more like 15, if that. They're not hideously jerky, but this still ain't no theatrical production.

The quality of the mono sound is fine; there's a noticeable "underwater" effect, but it's not offensive. The little playback speaker in the camera is quite acceptable, too.

The Sony also has an "e-mail" image mode, which takes a picture as normal, but also saves a 20-or-so-kilobyte 320 by 240 version of the image as the only frame of a five second MPEG movie file, with sound. This is a nice, cross-compatible, compact format for picture-with-sound-clip, and the file is only about 60 kilobytes, and thus thoroughly e-mailable. It'd be nice if you could record more than five seconds of sound if you wanted to, but it's OK as it stands.

Sound

Apart from the DSC-F505's true multimedia capabilities, both of these cameras are also able to make noises to tell you when things happen. Fortunately, both of them can be told to clam up as well. The Olympus just beeps when it has, for instance, successfully focussed on something. The Sony can beep when it does things, but can also play a cheesy click-whir noise when you take a picture. This gets old pretty fast.

Burst mode

One of the failings of many digicams is that they can't take multiple pictures in quick succession, like a motor-drive film camera. Given that they often take a few seconds to autofocus and then squeeze off a shot, it can be difficult to catch the moment you want, if you're aiming at a moving target.

The C-2500L, like many better recent digicams, has an on-board RAM buffer that lets it take pictures in "burst mode". You can take up to five shots in quick succession - about six seconds for the lot of them - if you don't use the flash. Since the flash is not a particularly speedy speedlight, and you need to wait for it to charge, a five-shot burst of flash pictures takes about 11 seconds.

Pleasingly, the five image burst mode buffer (changing resolution makes no difference - it's always five shots, presumably because it buffers the raw data from the CCD) works in such a way that you don't have to wait for it to empty before you can add another shot. There's an indicator on the C-2500L's top display that shows how many images are "stacked up" in the buffer; if it's less than five, you can take another shot right away.

You have to use the setup menu to turn burst mode on, which is a bit annoying even though the drive mode is the very first item on the list. A button to change modes would have been nice, or a change so that the camera remembers what mode it's in; if you turn the C-2500L off, it reverts to the single-image drive mode. If it's left idle and automatically turns itself off, though, it remembers its previous settings when woken up again.

The DSC-F505 has no burst mode, as such, but it does have its video record function. If the low resolution and high compression of the videos it makes are good enough for your purpose, you can grab whatever frames you want out of them.

Neither camera can match the abilities of a motor-drive 35mm, which can churn through a whole 36 shot reel of film in seconds if required. But there's a lot less wastage; by using the Olympus' burst mode, you can immediately review your pictures and delete some or all of them.

Video out

Both cameras have a video out connection, which lets you plug them into any composite video connector (for an explanation of what composite video is, see my guide here) for image playback. This lets you, for instance, take a load of pictures at a party and then play them all back as a slide show on the TV before everyone goes home. Or you can use the feature for business presentations, or dumping pictures to video tape, or whatever.

If you're a studio photographer that wants to use a TV or video monitor as a giant viewfinder, the C-2500L is not for you. Its video out can't do anything its screen can't do, so it's good for reviewing and menus only, thank you.

The DSC-F505, on the other hand, has a video output system as simple to use as many of its other features. Plug the A/V output cable into the yellow jack on the back panel, and the LCD goes blank; anything that would normally appear on the LCD now goes to whatever's at the other end of the composite video lead. This means you can use a TV to frame your pictures, or even plug the DSC-F505 into a VCR, put it in Still or Movie mode, hit Record on the VCR, and use the combination as a rather inelegant video camera. Or, if you've got a video capture board in your PC, the DSC-F505 can be pressed into service as a webcam.

The audio output only does anything when the speaker normally would, so you can't record sound to a VCR along with the image.

The C-2500L can do a sequenced slideshow (both cameras let you pick which images to display in the slideshow), and also lets you flick through images using the remote control, so you can use it like a manual-control slide projector. For the Sony, you have to have your hands on the camera to do anything but a sequenced slideshow.

The DSC-F505 can output to either PAL or NTSC video devices (also explained in my guide) with a simple menu selection. Its video heritage shows through clearly here; the exact shutter speeds it uses vary depending on whether it's set to PAL or NTSC. If you want the slowest, 1/6th second shutter speed, for instance, you have to pick PAL mode. Otherwise 1/8th is the slowest. You can effectively double these exposures with the second of the camera's two dim-light exposure modes, but you're still not really in long-exposure territory.

The Olympus comes in separate PAL and NTSC versions, and can't be switched between them.

Printing

The images from both of these cameras have enough resolution to be printed on a modern photo-quality inkjet in sizes up to about eight by six inches, before you'll start to see fuzziness. You can actually go a fair bit higher before the printout will start to look seriously pixelated.

The Olympus can write Direct Print Order Form (DPOF) data to either of its memory cards, so you can plug them into any compatible photo printer, like for example Olympus' own P-330, and have the images you want print out. You can select what pictures you want to print at your leisure, how many copies of each to print, whether to mirror the image, whether to print 16-up index sheets, and whether you want to include the date and time on each image. There's a special setting on the rotary mode selector just for the print setup function, which may annoy people who never intend to go anywhere near a DPF printer, but will do their printing through their ordinary PC.

The Sony also supports DPOF, but only the mark-to-print function, not the others.

Tripod mounting

Both cameras have solid, metal-thread tripod mounts. The Olympus mount is in the usual in-line-with-the-lens location, but the Sony one's moved forward onto its oversized lens barrel. The Sony mount also has a camcorder-type hole to receive the spring-loaded pin on many tripod plates; the hole doesn't really help you line the plate up much, though.

When tripod mounted, the Olympus battery door and the cover over its side connectors are difficult to access. It's easy enough to just pop the camera off the tripod, leaving the plate screwed on, though.

None of the Sony's functions are impeded by tripod mounting. The Sony's swivelling LCD also still swivels just fine when it's on a tripod. This makes it easier to use on a tripod that's set to an awkward height (low for close-ups, high to see over a crowd...) than the Olympus.

Sharpening

C-2500L image sharpness in "Normal" and "Soft" mode

Many, if not most, consumer digicams do automatic in-camera sharpening of every picture they take. This is perfectly valid, if it's not overdone; the sharpened images are better, if you want a picture that needs minimum fiddling to look great.

But if you want to get just what the CCD sees and nothing more, in-camera sharpening is a pain. You can do your own sharpening in any decent paint program, and you'll get very fine control of the kind and amount of sharpening you want to apply. When you're scaling and then sharpening images, as happens all the time in Web publishing work, you'll get a slightly higher quality result if the camera hasn't sharpened the original image. Pro imaging folks can't stand automatic in-camera sharpening.

For that reason, it's nice that the Olympus lets you turn off its standard sharpening. It conceals what it's doing, though, by calling the sharpened mode "Normal" and the un-sharpened mode "Soft".

Essentially, when you're just taking happy snaps, Normal mode is what you want, and for pictures you intend to fool around with, Soft mode is probably better. It's conceivable, though, that the C-2500L actually does slightly soften images when it's in Soft mode, because Normal mode isn't heavily sharpened but does seem unusually sharp in comparison. Opinions differ on whether Soft mode actually is suspiciously soft, though. If there's softening, it's very subtle.

You can't turn off the Sony's built-in sharpening. This really isn't a big handicap, though; purists will hate the auto-sharpen as much as they hate the absence of a super-low-compression mode, but for pretty much all real purposes neither of these shortcomings makes the Sony a worse camera.

Manuals

The Olympus manual is a traditional camera manual - three languages per page, and slightly obscure layout. It tells you everything you need, with plenty of handy hints for unskilled photographers, but it's not as easy to find one particular piece of information as it might be.

Sony's manual for the DSC-F505 is noticeably better. The manual I checked out is an English/Spanish number, but it splits its two sections down the middle, versus the Olympus approach of putting English, French and German on each page.

Semi-auto and manual modes

Both cameras offer semi-automatic modes. The only semi-auto mode on the Olympus is aperture priority, where you set which of the two possible aperture settings you want and the camera tries to automatically pick an appropriate shutter speed for the scene. Shutter priority is the same as aperture priority but the other way around; Olympus didn't give the C-2500L shutter priority, which is fair enough since it only has two aperture settings to choose from.

The DCS-F505 has both aperture and shutter priority modes, but that's as far as manual control goes for the Sony. The Olympus has full manual control as well, allowing you to specify the shutter speed and aperture you want.

The possible shutter speeds deliver a win for the Olympus. In automatic mode, the C-2500L can pick any of 37 shutter speeds from 1/2 to 1/10,000 of a second. Go to manual mode and you get access to another eight exposures, all the way up to eight seconds.

Incidentally, if you use the C-2500L's ISO adjustment, each doubling of the sensitivity halves the maximum exposure time you can set. You can only do two second exposures if you use the ISO 400 setting. Since the only reason you'd use the ISO-and-image-noise boost feature is because you wanted to use faster shutter speeds, though, this doesn't matter.

The Sony's possible shutter speeds are much less impressive than the Olympus camera's. When set to PAL mode it can do between 1/6 and 1/600 of a second, with only 12 possible speeds. 12 speeds are also available if the DSC-F505 is set to NTSC mode, now with a range from 1/8 to 1/725. Only the 1/100 speed shared between the two modes. I strongly doubt you'd see any real difference between the modes except at the slowest shutter speeds, in dim conditions; 1/6th is good for 33% more light than 1/8th. The second of the two "twilight" auto-exposure modes lets the Sony effectively double its exposure times, but it's still no long-exposure camera.

Given that the Sony has seven aperture settings available to it versus the Olympus' two, it actually has almost as many possible exposure combinations at any given time - 84, against 90 for the Olympus.

In reality, the Olympus' extreme shutter settings are not terribly useful, just as the Sony's top F-stops probably won't see action that often. With only ISO 100 sensitivity, 1/10,000 with either aperture setting makes high noon look like dusk. Wind up the sensitivity and 1/10,000 lets you get quite sharp pictures of fast-moving objects which aren't conveniently illuminated by a nearby 40 megaton airburst, but the extra noise from the artificial sensitivity enhancement means you still don't get particularly marvellous pictures.

Likewise, the C-2500L's really long shutter times may be great if you want to do artistic experiments (an excellent application for digicams, where mistakes don't cost money...), but they're no use for everyday photography. Long exposure times are a great antidote for poor sensitivity if you're shooting a still life, but most people aren't.

Both cameras have exposure compensation - you can manually tweak their automatic exposure calculations up or down. The Olympus has a special button for this purpose next to the shutter button; hold it down and select left or right on the four-way button on the back and you can boost or cut the auto-exposure by up to two F-stops each way, in 1/3rd stop increments.

The Sony lets you tweak the auto-exposure up to 1.5EV (Exposure Value, a catch-all unit for the brightness of a scene, covering the amount of light coming into a camera due to both aperture and shutter speed) either way, in 0.5EV increments. But you have to use a menu to do it.

Both cameras also let you set spot metering, so subjects drastically different from the background brightness can be photographed properly with the auto settings. Your black cat on a white bedspread will thus come out properly.

Long exposures

With up to eight second exposure times and first or second curtain flash, the C-2500L can do proper long exposure photography.

The world doesn't need another headlight-trail shot, but here one is. The eight second exposure ability of the C-2500L lets you create pictures like this, and other long exposures that pull invisible detail out of dim scenes, turn wind-blown trees into ethereal confections, and so on.

Another eight second C-2500L exposure, in the Notable Local Landmarks series. Note the fuzzy-looking trees, which were blowing in the wind.

Then again...

...the Sony's superior zoom does a lot to make up for its dimmer image.

For really dark subjects the Sony's no good, but it can pull reasonable detail out of a scene with its 1/6th second exposure, as this shows.

This is a "dark field" image from the Olympus. It's what you get when you take an eight second exposure with the lens covered. At a glance, it looks nice and even, with no glowing corners - which is good - but it's actually liberally sprinkled with "hot pixels".

The number of hot pixels shown here is higher than I've seen from some other long-exposure-capable digicams, but the evenness of the background makes up for them.

C-2500L hot pixels, full size. They're dimmed very slightly by JPG compression. The white dot to the lower left is the only "full on" hot pixel on the CCD of the 2500L I tested. The distribution of hot pixels will vary from camera to camera.

Why are there hot pixels? Glad you asked.

Digital camera CCDs at ordinary temperatures doesn't produce a perfectly even signal strength. Some pixels on the CCD are "hotter" or more active than others, and the CCD produces generally higher signal levels than it should the closer you get to the warm amplifier connection in one corner.

This doesn't matter for a brief exposure - if a few pixels are 1% brighter than they should be, who cares - but in long exposure images the hot pixels show up as bright dots and the warm corner has a diffuse bluish-white glow. Editing these artefacts out of the image by hand is extremely tedious.

Fortunately, there's a fairly easy way around the problem, by using a dark field image. Cover the lens of the camera with something light-proof and take a picture with the same exposure time as the one you want to clean up. This will give you ONLY the speckles and glow. Now, in your favourite paint package, subtract this "dark field" image from the picture you want to clean. In Photoshop you can do this by loading both images, selecting the dark field image, hitting control-A to select all of it, hitting control-C to copy it, selecting the photo image, hitting control-V to paste the dark field as a new layer, and then setting that layer's blend mode in the layer palette to Difference.

Here's the dark field image with its levels stretched to exaggerate its oddities. The warm corner is obvious, and there are also some strange horizontal lines. These lines, particularly the prominent topmost one, are visible in long exposure images with the C-2500L.

Self-timer

Both cameras have a timer-shot mode, in which the camera takes a picture some seconds after pressing the button. Using the timer lets you get your hands off the camera, which minimises vibration, so it can be handy for tripod macro shots. It's especially handy for Super Macro mode on the Olympus. The timer's main reason for being, though, is of course to let the photographer get into the frame.

The Olympus supports timer mode via its remote, as well; in this mode, the camera waits only two seconds before taking the shot, presumably just so that you can get your remote-holding hand out of sight.

Reviewing

The C-2500L has standard digicam image review abilities. Four or nine images can be shown on the LCD screen in thumbnail mode, or you can look at just one image, hopping from image to image with the four-way button on the back. You can zoom in on an image until there's a 1:1 correspondence of LCD pixels to real image pixels, and scroll around the zoomed image by holding down the button next to the shutter button which, in shooting mode, does exposure compensation.

The C-2500L's review zoom mode doesn't let you scroll all around the image in the full, 4X zoom, but only around the area you previously saw in 2X. You have to zoom out again to 2X, move to the part you want to view at full detail, then zoom in again. This is not a major problem.