Swann Wireless Guardian and SpyCam

Review date: 9 May 2001. Last modified 03-Dec-2011.

Setting up a basic closed circuit TV system's simple enough. You get a camera and a monitor and some cable, you drill holes in some walls to run the wire, and you're in business. Cameras are cheap these days, and for your monitor you can use anything that takes a composite video input - any off-the-shelf TV, for instance. Proper security monitors may have more rugged construction and better electronics, and may have multiple switchable inputs as well, but they're also more expensive.

Cheap video cameras all have infra-red sensitivity. So you can stick an IR illuminator next to them and see your baby, or shop, or area frequented by interesting wildlife, while the area looks pitch black to the naked eye. Many cheap cameras have a microphone built in, too, so with another wire you can have sound to go with your vision.

All this is not something the average home or small office user is likely to be too keen on doing, though.

For a start, if you're in rented premises or just don't want to take to your walls with an auger bit, you can only run cables by doing inelegant things around the skirting boards and under the doors.

Gaff is likely to be involved.

It's not a professional looking solution, and it's a particularly insecure way to connect a security camera.

Recently, high frequency video transmission technology's become more affordable. There have been microwave video link gadgets for some time now - they're what's used on racing car cameras, for instance - but they've typically been pretty darn expensive. Now, though, low power 900 and 2400MHz video transmission gear that can get a good signal through a few walls without using large antennas is quite cheap.

Case in point: The Swann Wireless Guardian. It's a black and white camera and five inch monitor set, it uses a 900MHz radio link to transmit video and audio, it's got video and audio outputs so you can connect it to other gear, and it's got two channels so you can buy a second camera and switch between them.

The camera's got a switchable IR illuminator built in, and you can even run both camera and monitor from battery power, if you like.

The whole lot, delivered in Australia, costs $AU350.90.

Along with the Wireless Guardian kit, I got another Swann product, their tiny $AU143 (delivered) SpyCam.

But first, the Guardian.

The Wireless Guardian kit comprises the camera and monitor, a mains plugpack for each of them, and a screw-fix mounting bracket that lets you easily attach the camera to a wall. There's a thread on the bottom of the camera for the bracket-mount screw, but it's smaller than the normal tripod mount thread used by various other camera gear.

The camera

The monitor's antenna is internal, but the camera's got this hinge-and-swivel flat panel. For close range use - say, from one side of a room to the other - the antenna alignment doesn't matter, but for longer ranges a bit of fiddling will give you a better picture.

The camera's compact enough that you can easily hand hold it. An ergonomic tour de force it is not, but it'll do.

Here are the camera controls, and the four little holes over the microphone. The controls are simple enough - one switch for power, one for the IR illuminator, and a button to tell the camera which of its two broadcast channels to use.

The controls on the front of the monitor are similarly uncomplicated. Power, channel select, display disable switch, volume knob. The power button's got a two-colour LED that's green when all is well and turns amber if the monitor's supply voltage is low - which it was, when I accidentally connected the monitor to the camera's plugpack.

When you've only got one camera, it doesn't seem to matter which of the two channels you select on either the camera or the monitor. It just works no matter how it's set up.

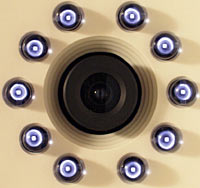

The camera lens, surrounded by the IR illuminator LEDs.

The lens is a normal small-aperture unit, as seen on umpteen cheap camera modules. It's fixed focus - or, to use the marketing term, "focus-free". Which is actually a good thing. This camera's not going to be used for a lot of demanding landscape photography or macrophotography; it's meant to be a low-hassle room monitor sort of critter, and mis-set focus is the last thing you want when you've just installed a camera high off the ground.

Plus, when you're only putting an image on a five inch screen, you've got a lot of tolerance for poor focus anyway.

The lens has a respectable field of view - not far shy of a full 90 degrees. If it were a 35mm film camera, it'd have perhaps a 23mm focal length. If you want to see a whole room using a camera sitting in the corner, this is the sort of lens you need.

Like all small wide-angle lenses, it's got considerable spherical distortion - that computer case in the background of the screenshot above doesn't actually have a curved front. But the image is fine apart from that.

Range

This is not one of those dodgy UHV/VHF telescopic-antenna video senders that has a hard time getting a clean signal into the next room.

The 900MHz transmitter on the camera, despite its small antenna (900MHz has a short wavelength, so you don't need a big aerial), had no trouble getting a signal from one side of my house to the other. Which was only about 14 metres as the crow flies, but that crow would have had to fly through about eight layers of brick on the way.

There was some definite noise on the picture and the audio at that range, which I couldn't completely get rid of by fiddling with the antenna, but it was perfectly watchable.

If I moved the camera and monitor much further apart, the image broke up no matter what I did with the camera antenna. With fewer walls in between, the range could be considerably better, depending on the number of people, trees and raindrops soaking up microwaves on the way. Swann don't quote a definite range figure for the Wireless Guardian.

Output

On the back of the Wireless Guardian monitor, there are knobs for contrast, brightness and vertical hold, the DC input jack, and two RCA sockets.

The sockets are for audio and video output, and they allow you to connect the Guardian to a bigger monitor or a VCR. You can leave the monitor's built-in screen and speaker active when you use the outputs, or you can disable the screen with the button provided for the purpose, turn down the audio, and just use the Guardian monitor as a receiver.

Power consumption

Neither the camera nor the monitor in the Wireless Guardian set consumes enough power to make much of an impact on the rotational speed of the disk in your electricity meter.

But both of them can also run from battery power.

Here's the camera's battery bay - it takes eight AA cells. Here it's running from alkalines, which work fine, but which can't be left in the camera if you connect it to its AC adapter. The camera automatically tries to charge its batteries when it's plugged in, which is bad news for alkalines.

From 9.6 volts - which is what it'll get from eight NiCd or NiMH rechargeable AA cells - the camera draws about 175 milliamps (mA) with its IR illuminator off, or about 215mA with it on. So if you use the 1.5 amp-hour (Ah) AA NiMH cells commonly available these days, you should get about seven to eight and a half hours of run time. This is very respectable performance, and makes the little camera suitable for carry-around duty, if you've got some reason to do that. Or you could stick it on top of your model tank, for that matter; the camera run time would not end up being the limiting factor.

The long run time from rechargeables also suggests that you can load the camera up with batteries even when you intend to use it from mains power, so it'll keep running even if there's a blackout or its mains plug gets pulled.

Unfortunately, it doesn't quite work that way. If the plugpack's connected to the camera, but not plugged into a live socket, the camera goes all weird (a technical term). With the IR illuminator off it still pretty much works, though the image is washed out; with the illuminator on, you get barely any picture.

It would appear that the camera's sending a big chunk of its power back through the dead plugpack, in the same way that some mobile phones will discharge themselves through their charger if you connect the charger to the phone, but don't plug the charger into the wall.

If you thought eight AAs was a lot, check this out. The monitor takes ten C cells. And, once again, can charge NiCd or NiMH cells when it's connected to its plugpack.

If you run it from alkalines, the monitor will probably still get roughly the 12 volts it expects; the high-ish current drain of the little screen will haul the high-internal-resistance alkalines' output voltage down from their nominal 1.5 volts per cell to something like the 1.2 volts of rechargeables.

Running from 12 volts, the monitor draws about 560mA with its display on. With the screen turned off, it only wants about 135mA.

You can get 4.5Ah NiMH C size NiCds for not much more than $AU13 each; 2.25Ah C size NiCds are maybe $AU6.25. US shoppers can do a bit better than that by buying from a place like Batteries America.

Even at a discount, though, it's a fair slab of cash when you're buying ten cells. If you want to use the monitor from batteries but save some money, a 7Ah 12 volt sealed lead acid (SLA) "gel cell" will only set you back about $AU45, or considerably less if you shop around. As I write this, Oatley Electronics have them for $AU25. A couple of alligator-clip leads will do to hook a gel cell up to the battery bay end terminals; for a more stylish result, anybody with a soldering iron can splice up a barrel plug lead that lets your lead acid battery emulate a plugpack.

Supplying half an amp isn't a big deal for any of these rechargeable technologies, so you'll get respectable life from all of them. Eight hours from the NiMH cells, four from the NiCds, about 12 hours from the SLA. You could wring some more out of the gel cell, but you shouldn't; lead acid batteries don't like being run dead flat, and last their longest if you keep them topped up.

Again, this is a pretty good result, no matter what kind of battery you use. The monitor's power consumption's low enough that you really could cart it out to the workshop and use it to check on the baby while you build your hot rod, or keep an eye on the backstage area to make sure nobody's lifting your stock at a trade show, or sit it in your tent with the camera up a tree shining IR light at nocturnal wildlife.

Since the monitor runs from 12 volts, you could also easily power it from a car cigarette lighter socket. You just need an appropriate cable.

Even loaded up with batteries, the monitor's readily portable; it's got a carry-handle moulded into the top.

Low light

The Wireless Guardian camera has excellent sensitivity. That's one of the good things about monochrome image sensors. Colour cameras have the same sort of sensor elements as black and white ones, but they have a mosaic of red, green and blue filters on top of the sensor, and build their image of the coloured world from the different response of the pattern of differently filtered pixels.

Black and white cameras don't have the filters eating the incoming photons, which gives them better sensitivity.

The upshot of this is that the Wireless Guardian camera, even without its IR illuminator turned on, can see noticeably better in the dark than can a human with normal eyesight. Magic it ain't, good it is.

Things get even better if you turn on the illuminator.

In a very dim room, where I couldn't quite read the un-backlit display on the top of my camera, the Guardian camera can see vague outlines, but doesn't really give you anything worthwhile.

Click on the illuminator, though, and you get this. Only on the Guardian's screen, though; the IR illumination's invisible to the naked eye.

Here, the subjects are only about 30cm in front of the camera, so it's actually overexposing somewhat. The LEDs are bright enough to adequately illuminate a not-especially-reflective target about three metres away. They can pretty much light the camera's whole field of view in many rooms.

The human eye can't see the radiation from the illuminator LEDs...

...but solid state image sensors can. This is my Olympus digital camera's view of the illuminator when it's active.

If there's not enough light from the built in illuminator, you can strap another after-market illuminator to the side of the camera, or install various other IR light fittings. Any incandescent light source can be turned into a not very efficient near-IR illuminator with a filter; there are various purpose-built options, too.

On to the James Bond product.

The SpyCam

The Swann SpyCam is a really small colour video camera.

How small?

This small (click the picture for a close-up).

The SpyCam is, essentially, just a "sugar cube" camera module in a a flanged case with holes that let you screw it onto something if you want. If you don't need the flanges, you could easily cut them off and make the camera even smaller.

The SpyCam kit gives you the camera itself, a nine volt plugpack to power it from the mains, and an adapter that lets you connect an ordinary nine volt battery as well. And a manual that suggests a few crafty concealment strategies, and some "fun" applications for the camera about which I reserve judgement.

The camera's got about five feet of cable, terminating in these two sockets. The barrel socket's for the power plug; the RCA socket is the composite video connector. It's a socket, not a plug, to make it easy to connect a normal RCA-to-RCA cable so you can have a lengthy cable run. There's a little male-to-male RCA cable included with the SpyCam, so you can easily connect the camera straight to anything that understands composite video. The camera will work with a TV or VCR, or with a computer with a video capture card. The SpyCam version I played with was PAL; there's an NTSC version as well.

From nine volts, the SpyCam draws only about 28.5mA. That's about twice what a nine volt alkaline battery wants to deliver, so you'll probably get less than 300mAh of capacity out of one at that current draw. That works out at around ten hours of run time.

Nine volt rechargeables won't care about that current draw, but they have pretty miserable capacity. Expect maybe five hours of run time from a true 9V NiMH rechargeable battery, or considerably less from one of the old style "9V" rechargeables, which are actually 7.2 volt and have really rotten capacity.

If you want a battery-powered SpyCam that'll run for ages, you can just use a pack of six alkalines. 30mA is low drain for any alkaline from AA size on upwards, so you'll get full capacity out of them. Six AA cells should give you three to four days of continuous run time, six C cells might last a fortnight, and six D cells ought to hang in there for three to four weeks.

If you don't want to put together a pack of larger cells - or just can't fit one in the cigarette pack you're using to hide your SpyCam - you can use a lithium 9V battery. They're expensive - more than $AU18 from Dick Smith Electronics here in Australia - but with more than twice the capacity of an alkaline 9V but better high current capacity (and lighter weight, if that matters to you), they ought to give you an easy day and a half of continuous run time, if not more.

The SpyCam's rated to run from seven to 13 volts, so you could run it from any 12 volt supply, as well.

Image quality

I was pleasantly surprised at how good a picture the SpyCam gave me when hooked up to my TV. The colour's a bit washed out and you have to adjust the tiny lens' focus manually if you want to get a sharp picture (the SpyCam doesn't have a fixed focus lens, and it's even wider angle than the Wireless Guardian camera). But considering its size, its image quality is superb.

We're talking roughly VHS quality, here. The resolution's nothing to write home about, but there are plenty of Video 8 and VHS-C camcorders that are no better.

In low light, the SpyCam video grains up, as you'd expect. Its automatic gain control is good (it doesn't flash and flicker as it hunts the right gain setting), but it also doesn't have a stutter-vision low light mode. So it has to use high gain in normally lit rooms at night, and the result's not great.

It's not rubbish, though; in a night-time room lit by one hundred watt bulb, the output from the SpyCam was perfectly tolerable. And considerably better than the results from certain $US2000 camcorders I could mention.

The SpyCam's CMOS image sensor puts a noticeable stationary grain all over everything when the camera's running in its higher gain modes, but that disappears when there's more light.

Overall

If you're looking for a tiny colour camera at a non-ridiculous price, the SpyCam's not bad. You can get black and white sugar cube modules for $US30 or so, but if you want colour and don't want to have to solder on your own power and output wires, the SpyCam's a plug and go option. Its focusable lens makes it very flexible; you can focus in arbitrarily close for surprisingly sharp macro shots, or set it to infinity. So it can give you quality monitoring of all sorts of things.

If you don't need something really teeny, though, there are plenty of palm-sized ready-to-go cameras that work the same as the SpyCam. Allthings Sales and Services in Australia sell a variety of cameras not much bigger than the SpyCam, and bare camera circuit boards as well. The larger cameras aren't a ton cheaper than the SpyCam - many are actually more expensive - but they generally have better lenses, higher sensitivity and/or superior resolution, and many have sound too.

If you want a colour video camera you can cram into a ping-pong ball, though, the SpyCam's pretty much it.

The Wireless Guardian is the product that really impressed me. For the money - $AU350.90 is only about $US180 at the moment - it's a remarkable piece of gear. It's got a robust wireless system, a battery option, sound as well as video, video output, a highly portable camera, infra-red illumination... the whole enchilada, basically. And for a decent price. Recommended.