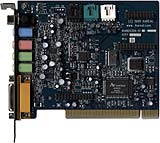

Aureal SQ2500 Vortex 2 sound card

Review date: 31 January 2000. Last modified 03-Dec-2011.

Aureal make what are, arguably, the best PC game sound cards in the world. Their Vortex 2 chipset lets you hear honest-to-goodness 3D sound from a multi-speaker or, better yet, headphone setup, and it handles fancy stuff like proper reflections from walls, and occlusion of sound by objects.

But, until recently, Aureal hadn't sold a single Aureal sound card.

This seeming paradox is explained by the fact that Aureal used to just make Vortex and Vortex 2 cards for other people to sell under their own brand names. This is more than some other big manufacturers do; some companies, like NVIDIA for instance, make only chipsets, and no retail cards at all.

It wasn't much of a leap, therefore, for Aureal to start making cards under their own name. Pretty much the only Vortex 2 cards they didn't make already were Xitel's Storm Platinum and the Turtle Beach Montego II (and you can tell; the Quadzilla version of the Montego II implements four speaker sound in a somewhat odd way. See my review here).

If anybody can make a good Vortex 2 board, you'd think it'd have to be Aureal. And you'd be right.

What you get

The SQ2500 is in the middle of Aureal's own-brand card range. Its US list price is $US99, with OEM (plain box, no software bundle) versions going for about $US50 from discounters. This puts it in the same price bracket as other manufacturers' Vortex 2 packages, and means you're looking at not much more than $AU100 for the OEM version and well under $AU250 for the full retail boxed card.

And what a box it is, by the way. Aureal appear to be shooting for the Box To Product Size Ratio Trophy for this year.

OK, so there are a couple of CDs and manuals in that big-ass box as well as the little SQ2500 itself. But there's also a heck of a lot of fresh air. Not that Aureal are at all unique in putting little things in huge boxes to make 'em stand out on the shelf; it's just a bit of a contrast from OEM cards, which often don't even have a box, just an anti-static bag.

Once you and your native guides have ventured forth into the trackless wastes of the SQ2500 box and retrieved the card, you'll find yourself looking at something not very different from various other full-specification Vortex 2s, which is hardly surprising under the circumstances.

The SQ2500's got four speaker output built in, via the usual 1/8th inch stereo jacks, and there's an RCA S/PDIF output as well. S/PDIF is only of interest to home theatre and home studio aficionados, and the output-only connector on the SQ2500 means it's only good for sending your nice clean digital music straight to a stand-alone recorder with S/PDIF input, or more likely sending Dolby AC3 audio to a surround sound decoder.

Some other single-board Vortex 2 cards have digital output, but to my knowledge the SQ2500 is the only one that has an RCA electrical connector, as opposed to a TOSLINK optical connector. There's no difference in sound quality between the two digital systems, but the electrical version is more popular on lower end gear.

Aureal's top-of-the-line SQ3500 Turbo, by the way, has a Dolby Digital decoder built right in, and can downmix the decoded surround sound to four speakers, two speakers or headphones. I hope to check out an SQ3500 shortly.

There's a line and a microphone input (more 1.8th inch jacks), and the usual joystick port which doubles, via an optional adaptor cable, as an MPU-401 compatible MIDI interface.

On the board there are three MPC2 standard inputs for CD, modem and auxiliary audio. You get only one MPC3 cable, but that's all most people are likely to need; many devices that use them come with a cable anyway, and you probably only have a CD-ROM drive to connect in any event. The modem connector is an input/output one, for voice modems that can work as an answering machine. Doing this with an internal modem, though, requires that you leave your computer turned on all the time.

(Incidentally, there are modems that can do the answering machine job with the computer off; I review one here).

There's also a header for a WaveBlaster standard MIDI daughter card, which can be piggybacked onto the board if you want to beef up its MIDI sounds.

The SQ2500 game bundle's a good one; you get the full versions of Psygnosis' third person dragon-riding fantasy-Tomb-Raider-With-More game Drakan: Order Of The Flame, and there's also Raven Software's third person magic-heavy combat-adventure Heretic II. Neither of these are brand spanking new games, but they're not very old, and they're both top-string titles, not just funny off-brand games that happen to have positional audio support. There's also a special "extended" seven level demo of Accolade's giant robot blast-up Slave Zero.

If you want the game bundle, it's decent value for the $US40 or so it'll tack onto the street price of the card. If you don't care, though, hang out for the OEM version.

You also get a good printed manual with the SQ2500, which explains in detail the whole installation and setup procedure, and goes on to tell you how to uninstall, troubleshoot common problems, and work the software. Manuals are getting more and more anaemic these days, and even the good ones commonly come only on CD, which isn't much use to a newbie scratching his head in front of his dismantled computer. It's nice to see proper documentation for a change.

One thing the manual doesn't mention is the WaveBlaster card connector on the board. Fortunately, pretty much no users are likely to care about this.

The SQ2500 also comes with the revision B incarnation of the AU8830 Vortex 2 chip, which is slightly faster than the 8830 on everybody else's Vortex 2 boards. This effect is only in the order of a few per cent, so you're not likely to actually notice it, but it's nice to know it's there.

Setting up

One of the big attractions of a card made by Aureal for Aureal is that the SQ2500 perfectly matches the Aureal reference drivers; whenever a new driver version comes out, it should work perfectly with the SQ2500.

That's not to say that the reference drivers don't behave themselves fine with other Vortex 2 boards that don't deviate from the reference design, but oddities like the Montego II Quadzilla need their own specially tweaked drivers to enable their extra features. In the Quadzilla's case, the extra features are the rear speaker and S/PDIF outputs on the board's daughter card. Run it with the reference drivers, and the daughter card might as well not be there.

The Rooms demo is the best of the Aureal A3D 2 show-off software

The SQ2500 comes with a driver CD containing reasonably up-to-date v2.040 drivers for Windows 95/98 and NT, plus demos, a DirectX updater, documentation and so on. The 2.040 drivers include the v2.25 version of A3D.

Aureal kept its users waiting for a new driver set with support for Creative's open EAX 2.0 standard for a while, but when I first wrote this the new drivers still weren't out. They are now, though; you can get the v2.048 drivers from here. The 2.040 or 2.041 drivers are perfectly functional, but EAX-free.

Sound quality

A Vortex 2 is a Vortex 2, as far as sound quality and 3D performance go. The Revision B chip is a tad faster, but sounds no better. Not that it needs to sound much better - A3D 2.0 is superb in most of the many games that support it. Sounds really do seem to come from distinct, 3-D locations, especially when you're using headphones.

All of the non-3D sound capabilities of the SQ2500 are well up to scratch, too; its inputs and outputs are very low noise, its recording quality is superb, and of course its digital S/PDIF output, being digital, is noise-free.

The very low noise design makes the SQ2500 perfectly suitable for studio work, provided of course that you can make do with just one external input jack. Make up cables for the internal CD and AUX IN jacks as well, though, and you could use a standard Vortex 2 card as a three channel stereo mixer without much trouble.

The SQ2500's MIDI output has an outrageous number of possible simultaneous voices (64 hardware, up to 512 more with software mixing), but the standard 4Mb instrument set is merely OK. It sounds acceptable, especially with the two simultaneous configurable effects you can layer on top of the music. But if you want something better, a whole different instrument set is only a download away - compatible DLS 1.0 sample sets can be had from various sites, like this one.

Four speaker mode

As with all four speaker Aureal-based cards, the fancy Head Related Transfer Function (HRTF) tricks that make you think sounds are coming from particular points apply only to the front speakers. The rear speakers only do stereo panning. Since the rear speakers only handle sounds that are actually meant to be behind you, though, this is not as big a problem as you might think. After all, who needs HRTFs to persuade you a sound is behind you when a speaker really is?

In four speaker mode, there can be occasional noticeable front-to-rear transfers, depending on where sounds are meant to be and where they're going. For the best 3D sound, I recommend headphones, but they have their own limitations. When you turn your 'phone-equipped head, the whole soundstage turns with you. You can move around inside the four-speaker sound space and the sounds will stay in the right place relative to the world you're supposed to be looking at through the screen. Then again, move too much when using speakers and, as you leave the "sweet spot" where all of the HRTF wizardry expects you to be, the illusion dissolves.

System performance

The Vortex 2 is a chip specially made to do A3D 2.0, unlike the earlier Vortex 1, which was a general purpose Digital Signal Processor (DSP), which required considerable help from the CPU to do fancy environmental effects and which therefore could cause a nasty loss of performance.

A3D 2.0 on the Vortex 2 still creates a CPU hit, but only because it's doing things that can't be done on the sound card - if the sound card is to do accurate wall reflections and sound occlusion, the computer has to provide the sound card driver with geometry information, just as it has to tell the video card driver what shape the world is.

How much of a hit you'll suffer depends on your processor and video card. The faster the video card is compared with the processor, the worse the performance loss will be; if the video card spends a lot of time waiting for the processor to feed it more geometry data, any processor time spent on A3D will be directly reflected in your game frame rates. If the processor out-speeds the video card, though, it'll have "spare" capacity and you may notice little to no loss of speed.

The upshot of this is that if you have a pretty current computer - say, a faster-than-300MHz P-II or better processor and a TNT2, Voodoo 3 or better graphics card - the performance hit from A3D should be perfectly acceptable, no matter how picky you are. If your computer is slower, then A3D for single player gaming (where the number of polygons being dealt with is typically lower, and the CPU thus less stressed) will be fine, and it's up to you to decide whether the loss of frame rate in multiplayer games makes up for the extra fun - and information - you get from hearing where things are happening.

Overall

There's nothing about the SQ2500 that makes it stunningly better, technically, than various other Vortex 2 cards, but its decent price and excellent bundled software give it an advantage. The four speaker output and S/PDIF connector put it up against the higher spec competing cards, and it gives 'em a run for their money. If you're in the market for a Vortex 2 card - and if you're an avid game player, you really should be - Aureal's branded venture into the market they've actually owned for a while is a darn good choice.

Recommended.

Review card kindly supplied by Aureal.

For a more in-depth treatment of Vortex 2 sound cards, see my earlier review of Turtle Beach's Montego II cards here.