ColorVision SpyderPRO with OptiCAL

Review date: 16 January 2004. Last modified 03-Dec-2011.

When you think about it, it's amazing that colour computer prints look anything like the original image on the screen.

The screen image is being created by a matrix of tiny red, green and blue splodges, which each emit light of varying brightness depending on the signal from their electron beam or thin film transistor (for CRT and LCD monitors, respectively).

The print, in contrast, is made up of at least four inks - cyan, magenta, yellow and black, with lighter versions of some of the colours added for finer control in true "photo quality" printers. The ink doesn't emit any light of its own, of course; all it does is reflect some portion of the light that hits it.

There are lots of different colour printer types, from domestic inkjets through high-output colour lasers to big commercial proofing machines, but all of them lay down some kind of coloured substance on the material on which they print, and that coloured substance is always fundamentally different in nature to the glowing splodges you were looking at before.

To make a screen image look like a print, regardless of what screen and what printer you use, you need colour calibration. Somebody, somewhere, needs to empirically measure what each printer and monitor does when it's told to print or display each shade of each colour. From those measurements, you can create a "profile" for each device (a widely-used standard for which has been created by the International Color Consortium) that compensates for its oddities. Similarly, profiles can be created for film viewed on a particular lightbox, slide projectors, and so on - but we're talking about digital, here. Get with the times.

You don't have to do this, of course. If all you're printing is business documents with the occasional picture of the new CEO in them on a bog standard four-colour inkjet, or if you're not using colour for more than highlights (or at all), then colour calibration is pointless.

Similarly, if you're just a home happy-snapper doing minimal domestic "digital darkroom" work on your digital photos, and you don't see anything very wrong with the results when you print them on your cheap-to-buy-but-expensive-to-run six-colour inkjet, then you might as well stick with what you've got.

Printer profiling also isn't likely to be necessary for most people, unless they're using after-market inks or unusual papers. One printer should work very much like another of the same model, it won't change with age, and printer manufacturers provide profile data for their products that covers various paper types.

Monitor profiling is another matter, though. Even monitors that're the exact same model will differ somewhat in their colour performance right out of the box. And CRTs, in particular, change with age. LCDs are more consistent over time, but they've got greater peculiarities in the first place.

Hence: This.

Pantone Colorvision USB Spyder - a monitor-calibrating colorimeter that normal humans can use without an advanced degree in optical physics. And it's pretty cheap, too.

The version of the Spyder I got for review is called the SpyderPRO. It's the same hardware as the basic Spyder package, but it comes with software called OptiCAL (and a three-machine license for it), plus a simpler package called PhotoCAL.

Here in Australia, Dirt Cheap Cameras sell this "SpyderPRO With OptiCAL" package for $AU449.06 (the US list price is $US249). You can also buy the Spyder with PhotoCAL only; that costs $AU351.02 from Dirt Cheap Cameras (its US list price is $US169).

The hardware

The Spyder's a good looking gadget. It also has a generously lengthy USB cable - more than 2.3 metres.

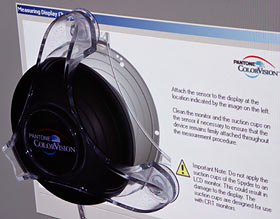

The colorimeter's seven-filter sensor hides behind this white diffuser panel.

It's important to prevent a screen profiler from seeing any light that isn't coming from the screen, so to use the Spyder with a CRT monitor you attach a rubber cup around the sensor. The cup seals against the screen, and keeps most ambient light out.

Unfortunately, a CRT screen has a pretty thick layer of glass between the outer surface, where the Spyder attaches, and the inner surface, where the phosphor is. It's thus impossible for the Spyder to exclude all ambient light. For best results you should, um, do it in the dark - at night, with no lights on in the room.

Or in the average overclocker's bedroom at high noon.

Try not to wake him.

To use the Spyder with an LCD screen - desktop or laptop - you have to change it around a bit. It's a bad idea to press hard on an LCD, so the suction cups are out, and LCDs also exhibit brightness changes as your angle of view moves up and down, so the Spyder has to be made to look at its little patch of the screen as vertically as possible.

This honeycombed baseplate replaces the rubber piece on the base of the Spyder, for LCD measurements.

Next, you pop off the suction cup assembly, and use this unlikely contraption to attach the Spyder to the LCD. One end of the hanger clips around the Spyder, the other has a counterbalancing weight on it, and a sliding angle-piece attaches the hanger to the top of the screen.

The arrangement actually works quite well, and should suit LCDs of all sizes.

Software

The meat of the Spyder packages is the ColorVision software itself, which I'll get to in a moment. But the SpyderPRO also comes with a trial version of Adobe's InDesign 2.0 desktop publishing package. It's not the latest version, and not the full version. Basically, it's just a way of avoiding an 80Mb download. The plain Spyder package lacks this CD; you're unlikely to miss it.

Every Spyder package also comes with Photoshop Album, which is described as "a $US49.99 value". But since Photoshop Album 2.0 Starter Edition is now a free download, and has a decent basic feature list, I think the full version is better described as "worth zero dollars plus whatever you'd pay for the extra full-version features."

Using it

I tested the Spyder on Windows XP, but it works with Win98, ME and 2000 as well, and Mac OS 9.x and higher.

As with many USB devices, you have to install the software before you plug in the Spyder. PhotoCAL and OptiCAL can both be installed at once, but there's not much reason to use PhotoCAL if you've paid the extra bucks for OptiCAL.

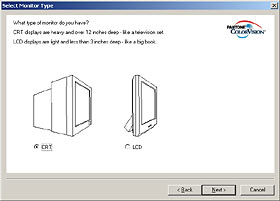

OptiCAL does everything that PhotoCAL can do, as you'd expect, plus considerably more. But PhotoCAL's simple wizard-based interface is easier to use. PhotoCAL makes no assumptions about the knowledge level of its user.

No assumptions.

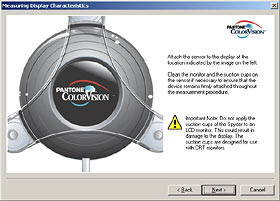

At the appropriate point in the wizard process, PhotoCAL tells you to stick the Spyder to the screen...

...which is easy enough to do.

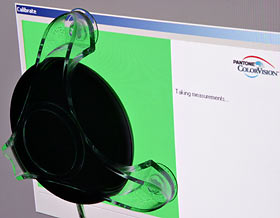

On my monitor, the PhotoCAL Spyder stick-on image happened to be about the same size as the actual Spyder, but this'll vary according to your monitor size and the resolution you're using. Unless you're using a 12 inch screen at 1600 by 1200, though, the ColorVision software's calibration patch should still be amply large.

PhotoCAL's automated calibration sequence takes a few minutes. At the end of it, it creates a profile for the monitor, and can optionally set that profile as the new default. And you're done. Well, except for wiping the suction cup marks off the screen.

PhotoCAL and OptiCAL don't automatically disable other monitor calibration software and/or profiles; you have to do that for yourself, before you calibrate. In WinXP, you can see whether there's already a calibration profile by going to Display Properties -> Settings -> Advanced -> Color Management; delete anything you find. You should also disable any exiting profiling software, like Adobe Gamma.

OptiCAL is a whole other story from the "home user" PhotoCAL.

For plain screen profiling, you can use OptiCAL like a less decorative PhotoCAL, or you can use it in "precision" mode which, after one regular profiling run, lets you (try to) adjust your monitor's white and black levels to match what the regular calibration run found, or to any other value you like.

And, as the above screenshot may suggest, OptiCAL does more.

You can see the differences between PhotoCAL and OptiCAL in table form here, or in prose here.

Monitors don't stop aging just because you've calibrated them; ColorVision recommend you recalibrate every two weeks. The general consensus seems to be that that's a bit excessive unless lives depend on the accuracy of your colour. In any case, OptiCAL can automatically warn you to recalibrate after a set interval, from six months (for the lazy) to one day (for people with nothing better to do).

From what I could tell, both PhotoCAL and OptiCAL worked just fine. It should be noted, however, that I'm an uneducated heathen with a cheap Samsung monitor that manages only about three-quarters of the recommended maximum luminance for colour-critical work. This is fine with me, though; super-bright screens may be necessary to deliver the same tonal range as a print, but they're not what I want to edit text on.

It should also be noted that the version of OptiCAL that's coming on the CD with the SpyderPRO package at the moment is not the version you should use. The CD version is v3.7.3, and all OptiCAL versions before v3.7.6 apparently have a non-trivial bug which has caused considerable gnashing of teeth. My review SpyderPRO came with the current v2.7 version of PhotoCAL, but its OptiCAL was old.

Fortunately, you can download free software updates from ColorVision here; v3.7.7 (or, according to its own About window v3.7.6-6...) is available as I write this.

You might also like to download the latest OptiCAL manual, but there haven't been any big feature changes. The most notable non-change is that OptiCAL still doesn't allow Windows users to calibrate two monitors separately. Twin monitors on a Mac - no problem. On Windows - nope.

Dual-monitor systems used to be pretty exotic, but these days umpteen consumer video cards come with dual outputs, and it's also easy to get various PCI video cards working as a secondary video adapter on a Windows box. The Spyder systems can still only calibrate the primary monitor, though; dual-monitor calibration for Windows is allegedly coming in the next version.

This isn't likely to be a disaster for many people, though, since dual-monitor graphics systems don't often use both screens for colour-critical work. If you've got a big monitor for the main image and a secondary screen with extra tools and palettes and such on it, there's no pressing reason to calibrate the second one. You can live with the lasso button looking a bit greenish.

Laptop users who sometimes use their LCD and sometimes use a CRT, by the way, can just make a profile for each screen in the normal way with OptiCAL or PhotoCAL.

Alternatives

Companies that sell colour calibration gear tend to oversell it. Their advertising invariably shows a wan and severely discoloured "Before" and a rich and vibrant "After" (example).

In reality, you don't have to spend a penny to make your screen image look pretty good.

Everybody who's doing any sort of imaging or design work - or play - on a computer should, at least, set their monitor up properly. But that doesn't cost anything, and you can find detailed or simple information about how to do it on the Web.

The next step up from this is software-only monitor calibration like that offered by Adobe Gamma and the several variably dodgy packages that tend to be bundled with video cards.

And then, there are other hardware options.

I haven't reviewed any other profilers in the same price range as the SpyderPRO. I think the current ColorVision software has dealt with the complaints people have had about the Spyder's accuracy compared to, in particular, GretagMacbeth's newer sub-$US250 Eye-One Display, though.

The Eye-One Display is definitely good, and isn't much more expensive than the SpyderPRO. The plain Spyder kit is a bit cheaper again, but the difference really shouldn't matter compared with the price of a half- decent PC, monitor, printer and digital camera setup.

The sky's the limit when you start talking professional colour calibration, of course. Most of the Eye-One products are much more expensive than the basic model, and GretagMacbeth will be happy to relieve you of more than $US6000 for a Spectrolino.

That's a much more capable colour calibration tool than a SpyderPRO, of course. It can do a lot more than just profile monitors.

And it is, as you might expect, utter overkill for most users. It's literally impossible to realise the benefits of really super-accurate calibration without considerable extra effort.

A monitor that's been calibrated with a high-priced professional spectrophotometer may be displaying the exact same colours as some other expensively-calibrated monitor, but your miserable human eyes won't see the colours the same way, unless the surrounding area's the same colour and lit the same way. Your brain's cunning little visual cortex does its own white balance adjustment to compensate for quite dramatic shifts in ambient light colour without drawing them to your attention. This is why it's hard to consciously notice the difference between yellow incandescent indoor light and blue indirect sky light unless you've just walked from one environment to the other.

To eliminate the problem of ambient light polluting the clarity of the visual palette, when this sort of thing is really critical, monitors are given black hoods and (ideally) people have to spend time under them to allow their eyes to adjust. Prints have to be viewed under a calibrated light source. There's no international certifying body for eyeballs yet, but I'll keep you posted.

If this sounds a bit over the top to you, you're right. This degree of calibration accuracy isn't at all critical for most people's applications. Spyder-level calibration, with the current software at least, is certainly more than adequate for me.

Overall

Monitor profiling isn't the end of the colour calibration story. Professionals don't trust manufacturers' profiles for their printers and scanners, either. But monitor profiling is all that most people need to do. And the Spyder and SpyderPRO seem to do it well enough.

Whether the Spyder is the best cheap monitor profiler on the market at the moment, I don't know. It certainly was, when the current LCD/CRT Spyder was introduced back in 2001 and soaked up various awards. But it ain't new any more.

It's easy to get a very bad impression of the Spyder if you surf the photo geek forums, but a lot of it's from the period in 2002 and 2003 between time when the profiling software bug was discovered and the time, quite a lot later, when it was fixed. Ignore the now-irrelevant bug complaints and there's a lot less Spyder-hate out there.

If the Spyder and SpyderPRO were still the only cheaper-than-your-whole-computer monitor profilers in existence, I'd have no hesitation recommending them to anybody who wants to take the next step up from just eyeballing their colour correction settings. Here in Australia, Dirt Cheap Cameras sell them for a fair price, compared with buying them from the States; their price for the SpyderPRO was high when I first wrote this review, but when I mentioned this to them they chopped it massively. Now it's still around $AU50 more than you could buy one for the USA from, but you get local warranty support for that extra money.

Anyway - as things stand, I like the Spyder just fine, but will reserve judgement on its relative value until I've put some other profilers through their paces.

Review SpyderPRO kindly provided by Dirt Cheap Cameras.